U.S. DECLINE IN RELATIVE TERMS WAS TO BE EXPECTED. NEW EMERGING NATIONS CAN—AND DO—LEARN FROM MORE DEVELOPED NATIONS AND LEAPFROG

HOWEVER, AMERICA HAS BEEN LOSING GROUND IN ABSOLUTE TERMS, AS WELL, IN SECTOR AFTER SECTOR

The TIME story is frustrating because it is really only a report on a report—and doesn’t get to grips with either the causes or the solutions.

Shoddy, but typical!

In that sense, its very mediocrity is illustrative of the subject it is writing about. In fact, the inadequacies of the U.S. main media play no small role in the decline—though some lesser known American publications, such as www.theatlantic.com are exceptional.

The frustrating thing is that the information is out there, but takes work to find. It is accessible, but not readily so.

Generally speaking, Americans aren’t being kept well informed about what is going on in other countries. Instead, there is a disconcerting tendency for much U.S. media to gloat over sundry foreign setbacks—rather than focusing on the numerous ways where other countries have been pulling ahead.

Schadenfreude has become the American media way—and it does not serve the country to advantage. It foments ignorance, but doesn’t make Americans feel content. They might not know the facts, or the scale of the problems, but uneasiness, to the point of fear, is pervasive.

One of the more telling manifestations of this is a truly massive breakdown in trust in virtually all U.S. institutions. The very structures that together constitute functional America are, by and large, held in low regard—from Big Business to the media, from the legal system to education.

Congress is trusted by fewer than 10 percent of the population. The military are trusted most—by over 70 percent—a decidedly unhealthy situation, particularly given the pervasive corruption and influence of the MICC (Military Industrial Congressional Complex), and its unhappy habit of engaging in a whole series of expensive, but inconclusive, wars.

What are the causes of U.S. decline?

I write about this subject regularly, but it really deserves an essay of length rather than the relative brevity of a blog. Nonetheless, let me risk a long blog and hazard a few reasons—since I have just criticized TIME for skipping this fundamental aspect.

Do not regard these few thoughts as my definitive contribution on the matter. They are more of a place-holder.

AN OBSOLETE CONSTITUTION.

The U.S. Constitution is an extraordinary document and has served the Nation well throughout much of its history. Yet, it was always a flawed document—as its initial tolerance of slavery demonstrated—and has needed modifying much more fundamentally, and regularly, than has actually happened.

The Founders expected it to be modified in the light of changing circumstances, so they would undoubtedly be both surprised, and shocked, to find it has been amended as little as it has. They created what they expected would be a dynamic, evolving document—but instead it has become, in many ways, an instrument of repression.

A core weakness is that, over time, the rich, in particular, have learned to game the Constitution to serve their purposes. In effect, the Constitution has become the tool that enables them to rig the system to their advantage. They are able to do this for a number of interconnected reasons.

- Through being able to pack the Supreme Court with business friendly judges—and thus use the court to block labor-friendly legislation. This has done untold damage to U.S. labor relations because it has minimized the incentives to compromise. Business knows it has all the power, so is damned if it is not going to use it.

- Through having corporations granted the same legal rights as people. This insanity has increased corporate power to excess and enabled it to gain substantial control of the political system.

- Through, mainly thanks to the Supreme Court, being able to make money in politics the dominant force—way ahead, in terms of impact, of the electoral process. In effect, the rich are able to do whatever they want largely unhindered. Since all power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, the consequences have not been positive.

CLASS WAR ON A TRULY EPIC SCALE

If nothing else, two world wars have taught Europe in particular—and more than a few other countries—that social justice is a more productive option than social oppression. This doesn’t mean that Europeans are kinder, nicer, or that human nature differs the other side of the Atlantic. Instead it means that bitter experience has taught Europeans that cooperation will almost certainly have a more positive outcome than confrontation.

As a consequence, you have the evolution of the EU, European soft power, and a legislative system that curbs corporate excess, and grants European workers substantial rights—including adequate vacations.

We are not talking a worker paradise here—merely a more humane, flexible, lower-risk, and motivating work environment

In contrast, the American rich—who have known little but success (if one ignores such tragedies as the Vietnam War) haven't developed a comparable mindset, and instead embarked on a campaign in the early 70s to restore corporate power to its dominant position, subdue workers, and destroy the trade union movement.

They had never really accepted the New Deal in the 30s, were too busy making money during, and after, WW II to care, but, in the 60s, were particularly rattled by such developments as the Civil Rights Act, the 1968 riots, and the rise of international competition—as other countries recovered from the devastation of WW II. They felt that the dominant status of American Business was at risk—and were determined to regain the high ground.

They didn’t have the numbers in terms of voters, but they had the money, the connections, the organizational skills, and the propaganda expertise so they had ever reason to be confident of success. Since they already knew how to manipulate the average American for commercial reasons—regardless of the merits of the products—they determined to use similar techniques for political ends. In fact, they soon appreciated that they could manipulate voters to both work, and vote, against their own interests. It was just a matter of playing on their fears and pressing the right emotional buttons. Racism and resentment proved to be particularly useful. Their faith in their expertise had not been misplaced.

That campaign, which has been waged with extraordinary viciousness, has certainly cut wage-costs, virtually destroyed the trade union movement in the private sector, corrupted the political system, and tilted the economic system to favor the rich, but it has also gutted the American Middle Class and destroyed much of its spirit.

Since the American Middle Class is America’s largest class, and the backbone of the economy in terms of income, numbers, and productivity, America has declined in parallel.

The U.S. is a house bitterly divided. Much of its famous ‘can-do’ spirit is canceled out by internal strife. It has been in a state of quiet civil war for over 40 years. The consequences have been—and continue to be—devastating.

A DEEPLY FLAWED AMERICAN BUSINESS MODEL (ABM)

The purpose of an economic system—whatever it may be(unfettered capitalism, European-style Social Democratic capitalism, socialism, or whatever)—should be to deliver the highest possible standard of living, and quality of life, to all the population in as risk-free manner as possible. Workers should be able to survive the inevitable vicissitudes of life—such as losing a job or suffering an accident—without excessive stress, or being driven into poverty. A successful economic system has to both encourage enterprise, yet promote resilience.

Such an objective is widely considered to require full employment, or, where that doesn’t exist, a social safety-net including adequate unemployment play, re-training if necessary, and help getting another job.

The goal is not equality,but equal opportunity—and reasonable equality consistent with the need to motivate and incentivize. As with most things, it is a question of balance—but one thing we do know is that excessive income and wealth inequality is socially divisive, and destructive, in a host of ways.

We also know that the U.S. is one of the most unequal countries in the world—with political, economic, judicial, and academic systems that are blatantly tilted towards favoring the rich. It is grossly unfair, unjust, anti-democratic, and—as recent productivity figures indicate—inefficient. Many other countries can offer a superior quality of life to their workers—including higher pay—and yet out-compete American firms. U.S. businesses are losing market leadership in sector after sector.

It is disillusioning. Workers are voting with their feet. Labor force participation is dropping like a stone.

The current ABM is widely touted as being the American Free Enterprise System. It really isn’t any more. What we have now is a heavily financialized system which has its hooks so deep into government, it is hard to tell where one part leaves off and the other commences. Corruption is rife. Conflicts of interest are routine to the point of being considered normal and socially acceptable.

The deficiencies of the current ABM would take a book to list but here are a few.

-

The ABM is neither delivering the jobs people need, nor the pay they require.

-

The ABM seems to have no social concern. American manufacturing plants have been closed down by the tens of thousands, and their jobs have been exported at will.

-

The ABM actively opposes any and all worker rights. These extend to such basics as paid vacation time of reasonable length, or maternity leave.

-

The ABM continues to make every effort, both legal and illegal, to destroy trade unions.

-

The ABM has shifted the burden of economic risk from its corporations to its workers.

-

The ABM has largely eliminated the defined pension.

-

Though competition is supposed to police private enterprise, the ABM has become increasingly concentrated and monopolistic. Most maket sectors are now dominate by a few large corporations which constitute an oligopoly.

-

The ABM is underinvesting and hoarding cash to the detriment of the National Interest.

-

The ABM is avoiding tax on an unprecedented scale. Business used to contribute about a third of the tax bases. The figure is now closer to 10 percent.

-

The ABM is not, in many cases, internationally competitive.

-

The ABM has suborned the political system and, quite blatantly, spends vast sums of money to buy politicians.

-

The ABM is focused on the entirely specious doctrine that management’s sole obligation is to maximize shareholder value. As a consequence it is fixated on share buybacks instead of productive investment in training, R&D, plant and equipment. It is a system without a moral code.

THE FOSTERING OF A TRULY ENORMOUS UNDERCLASS

The scale, scope, and sheer size of the American under-class is so large that it is hard not to form the opinion that fostering such a class is not government policy (or that of the ruling class).

It isn’t quite—in an overt declared sense—but the social safety net is so inadequate, and inconsistent, that the effect is much the same.

These problems are compounded by a widespread lack of social concern amongst Americans (to the point of resentment of the poor), deeply rooted racism, aggressive policing by heavily militarized police forces, a legal system that imprisons on a scale that few other countries come close to (the nearest is China with four times the population) policies towards felons that make it exceedingly hard for them to get back on their feet after they have served their time, and a self-righteous Republican party that seems to take egregious pleasure in the sufferings of the less fortunate—whether they be the poor, the long-term unemployed, or illegal immigrants.

The net effect of such a malign mixture of policies, prejudices, and penal legislation, is to create and perpetuate a substantial population that, in effect, constitutes a costly drag on society. And are perceived as just that—and treated accordingly in a self-perpetuating cycle of despair.

The truly enormous American subclass constitutes human waste on a scale that, just in itself, is an impediment to progress.

Nearly 50 million Americans are officially classified as living in poverty—and as many again are living paycheck to paycheck.

As for social mobility, it is significantly lower than that of many other developed nations. If you are born poor in the U.S., the chances are that you will be badly educated, and will die poor. If you are born poor and black, you are highly likely to end up in prison as well.

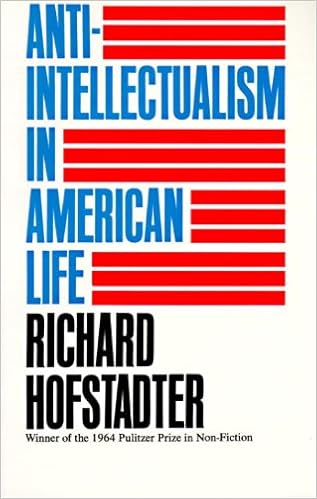

IGNORANCE

The U.S. contains pockets of the most astonishing talent, creativity, and expertise—but they are not sufficient to compensate for:

-

A mediocre to poor K-12 educational system which supplies largely under-educated people to the labor market.

-

An entirely inadequate apprenticeship system largely caused by the unwillingness of business to invest adequately in training.

-

A mixed college and university third level educational system which, at it best, is world class, but which is excessively expensive, socially divisive, and which is largely mediocre.

-

Media, which are largely for-profit and which focus on distraction and entertainment to the near exclusion of information.

-

A cradle to the grave diet of commercial and political propaganda which conditions, distracts, and confuses, but does little to communicate anything resembling the truth.

The cumulative effect of all this is to produce a population that, overall, not only doesn’t the skill levels to compete internationally, but which lacks the necessary qualities to function to full effect in the home market.

These inadequacies show up across the board in business, government, academia, and politically—and not only are self-perpetuating, but have a deadening effect on both creativity and productivity.

It is not that the talent isn’t there. It almost certainly is. But it is not cultivated—and then what remains is dulled, and then destroyed, by the pressures, cruelties, and distractions of the American Way of Life.

This is not a compassionate society. Individually, Americans can be exceedingly caring and compassionate, but the society they have created does not boast such qualities. Indeed, it has a tendency—as its prison system demonstrates—to be self-righteous, ignorant, and brutal.

A major manifestation of American ignorance is an unwillingness to learn from abroad—which, of course, perpetuates the ignorance.

Yet the answers, all too often, are in plain sight—and relatively straightforward. Ignorance apart, typically they are not adopted because of ideology, or because of some vested interest which benefits from the status quo. The concept of doing something for the common good seems to be less accepted in the U.S. than in other developed nations. Self-interest rules—and blocks.

THE WRONG INVESTMENT CHOICES.

Most developed nations attach great importance to government investment—and focus primarily on infrastructure and the welfare of the population. They also spend on defense, but try and keep that portion—which they know yields fewer practical benefits—to a minimum. They take the view that there are better options than war in most situations, and that investments in infrastructure and education, for example, yield a higher return than money spent on weaponry.

The U.S., where policy is significantly influenced by the MICC (Military Industrial Congressional Complex) and the Republican Party (which opposes almost all expenditure except on defense) marches to the beat of a very different financial drum, and has largely prioritized defense since WW II. As a consequences, numerous other important priorities have been neglected.

The point that people generally miss is the scale of this neglect. If you start counting from the end of WW II, it has now been going on for 70 years. That adds up to a waste and an investment deficit on an incalculable scale—not to mention a whole string of wars where the U.S. has not done too well.

A major reason for the U.S. decline is that it has spent its money—vast sums of it—on the wrong things. It has invested irresponsibly—and the consequences are self-evident.

A NATION THAT DOESN’T KNOW WHERE IT IS GOING

On the time-proven basis that if you don’t know where you are going, it is rather hard to get there, most developed nations plan.

They don’t micro-manage Soviet-Union style. Instead, they determine broad goals, and then, generally speaking, try and reach them through a blend of government action, persuasion and private initiatives.

Most successful nations today run mixed economies where what counts is what works. Pragmatism tends to be a great deal more common than ideology—even in officially communist countries like China, Vietnam, and Cuba.

U.S. business plans—as do government departments and most other institutions—but the Federal Government, as a whole, doesn’t plan both for for ideological reasons, and because its primary base of support—Big Business—doesn’t want any government interference.

It would be unfair to say that the U.S.government doesn’t plan at all—because policy statements are made by heads of departments and others at various times, but it certainly doesn’t plan in the integrated way other nations do—and this lack puts it at a serious disadvantage.

To make matters worse, the Federal Government is nearly entirely dependent on Congress if it wants to do anything—except make war—so the U.S. has a system which not only doesn’t plan, but—crucially—lacks the ability to execute with any degree of predictability (except where war is concerned).

A government which isn’t permitted to plan—and is prevented from executing in any kind of a rational and orderly fashion (and which is staffed by under-educated people) is unlikely to be an effective government—no matter who is president.

That situation is further compounded by Congressional gridlock and a Republican party which values ideology ahead of data—and blocks any initiatives except expenditure on defense.

Can the U.S. decline be reversed?

The good news is that virtually all—if not all—of the issues that underpin America’s decline (which I haven’t come close to listing) are, on the face of it, eminently resolvable within a manageable amount of time.

These are not wicked problems. In most cases, these are problems where the answers are known—and are probably already in effect in some other country.

The bad news is that the American Way of Life, deeply flawed though it may be, has such astonishing momentum as to be exceedingly hard to change.

If nothing else, American are conditioned to be American to a degree that the most fanatical Taliban might envy (where blind faith is concerned). And fundamental to the American Way of Life is the belief that the American Way is the best way, and superior to any, and all, alternatives. So why change! Facts don’t much enter into the picture here.

The simplest change is difficult in this context—and the sheer number of issues is daunting. On top of that, whereas Europe is well-educated, outward-looking, and multilingual (which brings cognitive advantages in addition to language skills)—because geography makes that virtually essential—under-educated America, because of its scale and location—and because of its media and culture—tends towards the insular

I have spent 14 years in the States, and was optimistic that the American decline could be reversed for much of that time.

More recently, as I contemplate the numerous ways in which other countries have been pulling ahead, I have begun to wonder.

On the one hand, I have long expected Americans to wake up and re-assess their extremely problematic situation—and you would be hard to encounter a more effective wake-up call than the Great Recession—but, somehow, there is always another distraction to prevent Americans from focusing on the real issues. America’s movers and shakers have a truly remarkable talent for manipulating public opinion away from issues of consequence—with distraction being the primary, and most effective tool. The most recent is probably ISIS who have distracted so effectively you would have to wonder if they weren’t a creation of America’s ultra-rich.

In fact, not only was the financial sector—which caused the Great Recession—bailed out with taxpayer money—but it has been allowed to make the whole situation worse. The big banks are now bigger and stronger than ever—and the poor, who suffered most, are now poorer. It is as if the U.S. population has learned nothing.

That is not entirely true. Interested observers, who have monitored the situation closely, have learned that the rot, that pervades the U.S. at present, is deeper and more destructive than our worst fears, and that the elite who control the country are even better entrenched. These findings, based upon much data about the truly appalling behavior of the Big Banks, and others within the financial sector, do not yield grounds for optimism.

In addition, Americans are conditioned to believe that the U.S. is “The Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave,”—together with all its associated myths and clichés—so are extraordinarily reluctant to believe, in any public way, that the U.S. is in the mess it is in. To freely and openly admit something so intrinsically un-American is a denial of their birthright—just too much for a red-blooded American to succeed.

What they believe privately is another matter. All the research suggests a massive loss of confidence in America which, nonetheless, doesn’t seem to be sufficient to incentivize most Americans to organize for fundamental change. It’s as if the whole nation is in denial—quietly but desperately worried, but (mostly) remaining silent.

As a consequence, I am no longer convinced that the American juggernaut is capable of changing course in time. The momentum of a mighty nation like the United States is near impossible to deflect, let alone to stop.

To paraphrase Stalin (who was talking about firepower) “Momentum has a quality of its own.”

Unfortunately, much of that unstoppable momentum is heading in the wrong direction.

For the sake of my many American friends, and the deep affection I feel for the U.S., I truly hope my conclusions are wrong.

They are not, of course, mine alone.

Why America is Falling Behind the Rest of the World

TIME.com · by Jill Hamburg Coplan / Fortune · July 21, 2015  Spencer Platt—Getty Images A homeless man sleeps under an American Flag blanket on a park bench in the Brooklyn borough of New York City on Sept. 10, 2013.

Spencer Platt—Getty Images A homeless man sleeps under an American Flag blanket on a park bench in the Brooklyn borough of New York City on Sept. 10, 2013.

12 signs of the decline of the U.S.A.

America is declining, in large and important measures, yet policymakers aren’t paying attention. So argues a new academic paper, pulling together previously published data.

Consider this:

- America’s child poverty levels are worse than in any developed country anywhere, including Greece, devastated by a euro crisis, and eastern European nations such as Poland, Lithuania and Estonia.

- Median adult wealth in the US ($39,000) is 27th globally, putting it behind Cyprus, Taiwan, and Ireland.

- Even when “life satisfaction” is measured, America ranks #12, behind Israel, Sweden and Australia.

Overall, America’s per capita wealth, health and education measures are mediocre for a highly industrialized nation. Well-being metrics, perceptions of corruption, quality and cost of basic services, are sliding, too. Healthcare and education spending are funding bloated administrations even while human outcomes sink, the authors say.

“We looked at very broad measures, and at individual measures, too,” said co-author Hershey H. Friedman, a business professor at Brooklyn College – City University of New York. The most dangerous sign they saw: rising income and wealth inequality, which slow growth and can spark instability, the authors say.

“Capitalism has been amazingly successful,” write Friedman and co-author Sarah Hertz of Empire State College. But it has grown so unfettered, predatory, so exclusionary, it’s become, in effect, crony capitalism. Now places like Qatar and Romania, “countries you wouldn’t expect to be, are doing better than us,” said Friedman.

12 signs of the decline of the U.S.A.

America is declining, in large and important measures, yet policymakers aren’t paying attention. So argues a new academic paper, pulling together previously published data.

Consider this:

America’s child poverty levels are worse than in any developed country anywhere, including Greece, devastated by a euro crisis, and eastern European nations such as Poland, Lithuania and Estonia.

Median adult wealth in the US ($39,000) is 27th globally, putting it behind Cyprus, Taiwan, and Ireland.

Even when “life satisfaction” is measured, America ranks #12, behind Israel, Sweden and Australia.

Overall, America’s per capita wealth, health and education measures are mediocre for a highly industrialized nation. Well-being metrics, perceptions of corruption, quality and cost of basic services, are sliding, too. Healthcare and education spending are funding bloated administrations even while human outcomes sink, the authors say.

“We looked at very broad measures, and at individual measures, too,” said co-author Hershey H. Friedman, a business professor at Brooklyn College – City University of New York. The most dangerous sign they saw: rising income and wealth inequality, which slow growth and can spark instability, the authors say.

“Capitalism has been amazingly successful,” write Friedman and co-author Sarah Hertz of Empire State College. But it has grown so unfettered, predatory, so exclusionary, it’s become, in effect, crony capitalism. Now places like Qatar and Romania, “countries you wouldn’t expect to be, are doing better than us,” said Friedman.

“You can become a second-rate power very quickly,” added Hertz.

To be sure, the debate over whether America is on the decline has raged for years. The US National Intelligence Council said in its global trends report a decade ago American power was on a downward trajectory. Others making the case say the US is overstretched militarily, ill-prepared technologically, at-risk financially, or lacking dynamism in the face of influential, new competitors.

Arguing decline has been exaggerated, others point to a rising US stock market, manufacturing strength, a growing population, and a domestic energy boom.

The authors collect many previously published rankings, and the picture that emerges, however, is sobering:

1. Median household income

Rank of U.S.: 27th out of 27 high-income countries

Americans may feel like global leaders, but Spain, Cyprus and Qatar all havehigher median household incomesthan America’s (about $54,000). So does much of Europe and the industrialized world. Per capita median income in the US ($18,700) is also relatively low–and unchanged since 2000. A middle-classCanadian’s income is now higher.

2. Education and skills

Rank of U.S.: 16th out of 23 countries

The US ranked near the bottom in a skills survey by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, which examined European and other developed nations. In its Skills Outlook 2013, the US placed 16th in adult literacy, 21st in adult numeracy out of 23, and 14th in problem-solving. Spots in prestigious US universities are highly sought-after. Yet higher education, once an effective way out of poverty in the US, isn’t anymore – at least not for lower-income and minority students. The authors quote studies showing, for example, that today 80% of white college students attend Barron’s Top 500 schools, while 75% of black and Latino students go to two-year junior colleges or open-admissions (not Top 500) schools. Poor students are also far less likely to complete a degree.

3. Internet speed and access

Rank of U.S.: 16th out of 34 countries

Broadband access has become essential for industry to grow and flourish. Yet in the US, penetration is low and speed relatively slow versus wealthy nations—thought the cost of internet is among the highest ($0.04 per megabit per second in Japan, for example, versus $0.53 in the US). The problem may be too much concentration and too little competition in the industry, the authors suggest.

4. Health

Rank of U.S.: 33rd out of 145 countries

When it comes to its citizens’ health, in countries that are home to at least one million people, the US ranks below many other wealthy countries. More American women also are dying during pregnancy and childbirth, the authors note, quoting a Lancet study. For every 100,000 births in the United States, 18.5 women die. Saudi Arabia and Canada have half that maternal death rate.

5. People living below the poverty line

Rank of U.S.: 36th out of 162 countries, behind Morocco and Albania

Officially, 14.5% of Americans are impoverished — 45.3 million people–according to the latest US Census data. That’s a larger fraction of the population in poverty than Morocco and Albania (though how nations define poverty varies considerably). The elderly have Social Security, with its automatic cost-of-living adjustments, to thank, the authors say, for doing better: Few seniors (one in 10) are poor today versus 50 years ago (when it was one in three). Poverty is alsodown among African Americans. Now America’s poor are more often in their prime working years, or in households headed by single mothers.

6. Children in poverty

Rank of U.S.: 34th out of 35 countries surveyed

When UNICEF relative poverty – relative to the average in each society—the US ranked at the bottom, above only Romania, even as Americans are, on average, six times richer than Romanians. Children in all of Europe, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan fare better.

7. Income inequality

Rank of U.S.: Fourth highest inequality in the world.

The authors argue that the most severe inequality can be found in Chile, Mexico, Turkey — and the US. Citing the Gini coefficient, a common inequality metric, and data from Wall Street Journal/Mercer Human Resource Consulting, they say this inequality slows economic growth, impedes youths’ opportunities, and ultimately threatens the nation’s future (an OECD video explains). Worsening income inequality is also evident in the ratio of average CEO earnings to average workers’ pay. That ratio went from 24:1 in 1965 to 262:1 in 2005.

8. Prison population

Rank of U.S.: First out of 224 countries

More than 2.2 million Americans are in jail. Only China comes close, the authors write, with about 1.66 million.

9. Life satisfaction

Rank of U.S.: 17th out of 36 countries

The authors note Americans’ happiness score is only middling, according to the OECD Better Life Index. (The index measures how people evaluate their life as a whole rather than their current feelings.) People in New Zealand, Finland, and Israel rate higher in life satisfaction. A UN report had a similar finding.

10. Corruption

Rank of U.S.: 17th out of 175 countries.

Barbados and Luxembourg are ahead of the US when it comes to citizens’ perceptions of corruption. Americans view their country as “somewhat corrupt,” the authors note, according to Transparency International, a Berlin-based nonprofit. In a separate survey of American citizens, many said politicians don’t serve the majority’s interest, but are biased toward corporate lobbyists and the super-rich. “Special interest groups are gradually transforming the United States into an oligarchy,” the authors argue, “concerned only about the needs of the wealthy.”

11. Stability

Rank of U.S.: 20th out of 178 countries.

The Fragile States Index considers factors such as inequality, corruption, and factionalism. The US lags behind Portugal, Slovenia and Iceland.

12. Social progress index

Rank of U.S.: 16th out of 133 countries

A broad measure of social well-being, the index comprises 52 economic indicators such as access to clean water and air, access to advanced education, access to basic knowledge, and safety. Countries surpassing the US include Ireland, the UK, Iceland, and Canada.

“If America’s going to be great again, we’ve got to start fixing things,” Friedman said.

Jill Hamburg Coplan is a writer and editor and regular contributor to Fortune.

This article originally appeared on Fortune.com

Spencer Platt—Getty Images A homeless man sleeps under an American Flag blanket on a park bench in the Brooklyn borough of New York City on Sept. 10, 2013.

Spencer Platt—Getty Images A homeless man sleeps under an American Flag blanket on a park bench in the Brooklyn borough of New York City on Sept. 10, 2013.