A VIEW ABOUT VIEWS—DO WE REACT SPONTANEOUSLY, OR ARE WE CONDITIONED?

I often wonder about the extent to which our thoughts are conditioned—in contrast to whether they are original. I have to say, based upon observation, that conditioning wins out by a wide margin.

If true, such a conclusion has all kinds of implications—mostly disturbing. And it also raises serious questions about free will? Religion makes a great feature of free will; but, if we are as manipulated to the extent I believe we are, then free will has, at best, a supporting role. So, in essence, we are being conditioned to believe we have free will.

Who says the gods don’t have a sense of humor!

These thoughts arose because I have been thinking about the view from this apartment. I’m leaving the place shortly; and, after hearing one of the new owners rave (to excess) about the view, I have been wondering: Will I miss the view?

The apartment, itself, is another matter. It has been an excellent place to work from for the last couple of years—and, above all, quiet. As to the view, apart from the fact that it has been rather pleasant to be high up, it has left me unmoved.

In direct line of sight, it consists of some docks full of leisure craft. and a rather unattractive apartment building. True, Lake Washington is to my right, if I go out onto the balcony—chilly this time of year—but the wonders of Lake Washington leave me unmoved. It has none of the majesty and endless variety of the sea, nor the beauty of the small Irish lakes that dot Connemara in the West of Ireland. I first encountered them while on a walking tour during my early teems, and have returned many times to contemplate them—and I never cease to wonder. That part of the West is a wild land, and uniquely wonderful. In fact, as far as I am concerned, it is magic.

My late (and very special) friend, Niall Fallon, lived in that part of the world for some years—he was writing a book on the Spanish Armada amongst other things—and was less than flattering about the reality of day-to-day life in Connemara. Overall, he had a tough time making a living there. I seem to recall, he bred dogs there as well. We writers will try anything. Either way, it was not a successful time for him, though his book was excellent. He was not only a fine man, but an excellent writer.

My late (and very special) friend, Niall Fallon, lived in that part of the world for some years—he was writing a book on the Spanish Armada amongst other things—and was less than flattering about the reality of day-to-day life in Connemara. Overall, he had a tough time making a living there. I seem to recall, he bred dogs there as well. We writers will try anything. Either way, it was not a successful time for him, though his book was excellent. He was not only a fine man, but an excellent writer.

Nonetheless, after I had fallen in love with the Aran Islands as well, I based the protagonist of my first three books, Hugo Fitzduane, in that part of the world—albeit just off the coast on his very own (entirely fictional) island—and gave him an old Norman keep to live in into the bargain. A plain keep is a rectangular stone tower—normally a statement of dominance over a given area of land, and preferably within signaling distance of a neighbor who could send help if needed. It was a simple, but extremely powerful, system of control, and it underpinned the feudal system.

In Fitzduane’s case, his keep has been somewhat expanded to a size many would refer to as a castle—but it remains relatively small. This entirely fictional place is now as real to me as if it actually exists. I based it on several castles; but, arguably, the nearest to my mental model is Dunguaire. However, there are a number of distinct differences. The keep of Duncleeve (Fitzduane’s castle) has a flat roof—or fighting platform. Secondly, it is taller. Thirdly, it has a larger bawn or walled courtyard. And fourthly, it has a larger gatehouse complete with a portcullis. Still, Dunguaire does convey the general idea.

Was I conditioned to take to that wild, bleak, wind-and-rain swept, and stunningly beautiful part of the world—or did I react spontaneously?

My ego (which I try and regard with some skepticism, since it is scarcely unbiased) says I certainly was not conditioned—my parents, for instance, were not remotely interested in that part of the world, nor were any of my relations and mentors—but I guess I’ll never know. Certainly, I was impelled to visit the West on that first walking holiday for some reason.

These days, while Fitzduane and his island are forever in my mind, my own favorite locations are in South West France (Perigord Pourpre and Perigord Noir). The area was the scene of great contention between the English and the French back in the Middle Ages, and it is not hard to see why.

As best I can determine it, Perigord and Aquitaine overlap—which makes life very confusing. Aquitaine, which includes a whole chunk of the French Atlantic coast, was a kingdom in its day—and bordered on Spain.

I have thought of either living there—or at least spending some months there every year.

Much of my latest Fitzduane book, THE BLOOD OF GENERATIONS, is set there. It is the fourth in the series.

Will there be more Fitzduane books? I like to think so. I have written four so far. Seven seems a nice round total because I want to write other books as well. Nonetheless, it has been put to me—many times—that since Fitzduane hasn’t taken off like James Bond, I should abandon him.

Perhaps so, if money was my only goal. But it is not. The truth is that I am very fond of my fictional protagonist, have spent a great deal of time in his company, regard him as a fundamentally decent man (if somewhat prone to be dragged into adventures of some violence), and don’t regret growing old in his company. Beyond that, many of those readers who have discovered him, not only positively long for his return, but have said so in writing—and they tend to be impassioned.

Two impossible dreams? In these cases, I look forward to finding out.

The above is Aquitaine.

The above is Aquitaine.

Think Eleanor of Aquitaine who had an impressively contentious marriage to Henry II of England.

See also that marvelous movie The Lion In Winter starring Peter O’Toole and Katherine Hepburn. The movie makes a great deal more sense if one knows the historical background. Eleanor was a major historical figure—and Aquitaine was worth fighting for. That, they certainly did.

I run across quotes from Teddy Roosevelt frequently, have read about him a great deal, but have never actually read any of his original works.

I run across quotes from Teddy Roosevelt frequently, have read about him a great deal, but have never actually read any of his original works.

Packing continues, and I am beginning to solve some of the trickier problems. It is really not a mammoth operation, but books weigh heavy, and ring-binders in volume can be awkward. Unless packed tightly, the mechanisms can be damaged, and then they are virtually unfixable—and refuse to stand upright.

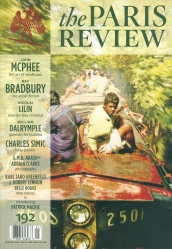

Packing continues, and I am beginning to solve some of the trickier problems. It is really not a mammoth operation, but books weigh heavy, and ring-binders in volume can be awkward. Unless packed tightly, the mechanisms can be damaged, and then they are virtually unfixable—and refuse to stand upright.  George Plimpton, decades ago and he managed to make them sound like frank conversations between friends—which frequently they were, because he knew everybody—and to draw out the personalities of his interviewees. As a consequence, the actual conversations tend to be candid, amusing, provocative, informative and thoroughly entertaining.

George Plimpton, decades ago and he managed to make them sound like frank conversations between friends—which frequently they were, because he knew everybody—and to draw out the personalities of his interviewees. As a consequence, the actual conversations tend to be candid, amusing, provocative, informative and thoroughly entertaining.

their jobs. That is a truly worrying statement.

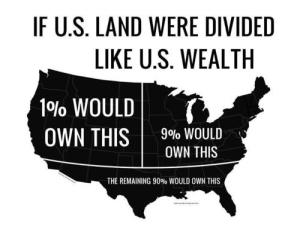

their jobs. That is a truly worrying statement.  Capital and labor made peace in Europe after World War II. There had been so much dissension, and so much blood had been spilled, that it seemed like the only sensible thing to do. Workers were given significant rights, and such arrangements have stood the test of time.

Capital and labor made peace in Europe after World War II. There had been so much dissension, and so much blood had been spilled, that it seemed like the only sensible thing to do. Workers were given significant rights, and such arrangements have stood the test of time. Recently, I have experienced a number of setbacks—so this topic is near and dear to my heart.

Recently, I have experienced a number of setbacks—so this topic is near and dear to my heart.  and a following wind—you’ll begin to get the hang of it.

and a following wind—you’ll begin to get the hang of it.  Shortly before my much loved grandmother, Vida Lentaigne died, I was inspired to write to her to say how much she meant to me.

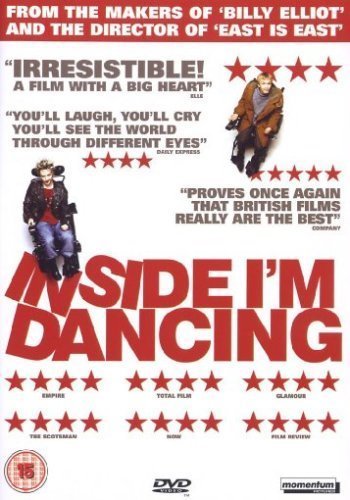

Shortly before my much loved grandmother, Vida Lentaigne died, I was inspired to write to her to say how much she meant to me.  The author of the letter was my son, Christian. He is an award-winning playwright who has also had the distinction of having one of his works made into an excellent, and very touching, movie:

The author of the letter was my son, Christian. He is an award-winning playwright who has also had the distinction of having one of his works made into an excellent, and very touching, movie: The movie was also marketed under a different title—RORY O’SHEA IS HERE.

The movie was also marketed under a different title—RORY O’SHEA IS HERE.  The idea of moving every year or two hovers somewhere between hopelessly impractical and insane to most people—though the U.S. military do it all the time. I guess that rather proves the point.

The idea of moving every year or two hovers somewhere between hopelessly impractical and insane to most people—though the U.S. military do it all the time. I guess that rather proves the point.

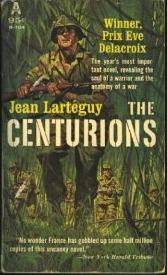

The full story of what happened in Corsica (rather a lot) will have to await my memoirs—but suffice to say that we did track down both the Legion and some bandits.

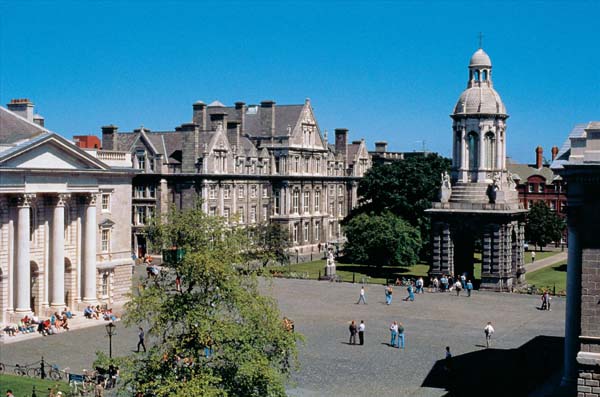

The full story of what happened in Corsica (rather a lot) will have to await my memoirs—but suffice to say that we did track down both the Legion and some bandits. Due to my mother’s quaint habit of enlisting me in boarding schools too young—a terrible thing to do to a kid no matter how bright—I entered university at sixteen to do a four year course, and graduated at the age of twenty.

Due to my mother’s quaint habit of enlisting me in boarding schools too young—a terrible thing to do to a kid no matter how bright—I entered university at sixteen to do a four year course, and graduated at the age of twenty.  A little while later, Bunny and I were at a party when someone mentioned that the French Foreign Legion had been disbanded following the failed attempt to overthrow President De Gaulle.

A little while later, Bunny and I were at a party when someone mentioned that the French Foreign Legion had been disbanded following the failed attempt to overthrow President De Gaulle.  I first ran across the French Legion through the books of P.C. Wren.

I first ran across the French Legion through the books of P.C. Wren.

Since I was about eleven when I read P.C. Wren, I never did enlist in the Legion, and it might have remained buried in the recesses of my mind. However, some years later, a quite extraordinary book appeared—which had a profound effect on my thinking and, though I did not realize it at the time, on the rest of my life.

Since I was about eleven when I read P.C. Wren, I never did enlist in the Legion, and it might have remained buried in the recesses of my mind. However, some years later, a quite extraordinary book appeared—which had a profound effect on my thinking and, though I did not realize it at the time, on the rest of my life.

My late (and very special) friend, Niall Fallon, lived in that part of the world for some years—he was writing a book on the Spanish Armada amongst other things—and was less than flattering about the reality of day-to-day life in Connemara. Overall, he had a tough time making a living there. I seem to recall, he bred dogs there as well. We writers will try anything. Either way, it was not a successful time for him, though his book was excellent. He was not only a fine man, but an excellent writer.

My late (and very special) friend, Niall Fallon, lived in that part of the world for some years—he was writing a book on the Spanish Armada amongst other things—and was less than flattering about the reality of day-to-day life in Connemara. Overall, he had a tough time making a living there. I seem to recall, he bred dogs there as well. We writers will try anything. Either way, it was not a successful time for him, though his book was excellent. He was not only a fine man, but an excellent writer.

The above is Aquitaine.

The above is Aquitaine.  Tina Rosenberg was the first freelance journalist to receive a five-year MacArthur Fellowship "genius" award. Her writings have appeared in The New Republic, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Harper's, and The New York Times Magazine. She is the author of the acclaimed Children of Cain: Violence and the Violent in Latin America, and The Haunted Land, Facing Europe's Ghosts After Communism. Formerly a Visiting Fellow at the National Security Archive, and a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute.

Tina Rosenberg was the first freelance journalist to receive a five-year MacArthur Fellowship "genius" award. Her writings have appeared in The New Republic, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Harper's, and The New York Times Magazine. She is the author of the acclaimed Children of Cain: Violence and the Violent in Latin America, and The Haunted Land, Facing Europe's Ghosts After Communism. Formerly a Visiting Fellow at the National Security Archive, and a senior fellow at the World Policy Institute.

It is noteworthy that again and again, when a less expensive alternative is put forward, that the military almost always opt for the more expensive options—even when the less expensive item is operationally superior. The reason for this is that a great many senior officers have plans to retire into the MICC—and the MICC is powered by the money flow emanating from the Department of Defense. The money flow is based on expensive weapons systems—on programs that last for decades like the F-35 aircraft. In fact, some would argue that the best weapons procurement programs—as far as the generals are concerned—are decades long programs that never result in a usable weapons system. However they do make excellent retirement platforms. Recall the Crusader artillery system that never saw the light of day—and the Comanche helicopter. They are far from unique, and kept the money flowing. And then there was the Future Combat System—a truly massive program that was supposed to transform the American Way of War; and which was given to Boeing to manage in a deal that neither reflected well on Boeing nor on the Army. Massive amounts of money have a disturbing tendency to corrupt.

It is noteworthy that again and again, when a less expensive alternative is put forward, that the military almost always opt for the more expensive options—even when the less expensive item is operationally superior. The reason for this is that a great many senior officers have plans to retire into the MICC—and the MICC is powered by the money flow emanating from the Department of Defense. The money flow is based on expensive weapons systems—on programs that last for decades like the F-35 aircraft. In fact, some would argue that the best weapons procurement programs—as far as the generals are concerned—are decades long programs that never result in a usable weapons system. However they do make excellent retirement platforms. Recall the Crusader artillery system that never saw the light of day—and the Comanche helicopter. They are far from unique, and kept the money flowing. And then there was the Future Combat System—a truly massive program that was supposed to transform the American Way of War; and which was given to Boeing to manage in a deal that neither reflected well on Boeing nor on the Army. Massive amounts of money have a disturbing tendency to corrupt.

One of the things I have learned in life is that –where the opposite sex is concerned—the unattainable is not necessarily as unattainable as one might think. Here the SAS motto—He Who Dares Wins—is worth considering.

One of the things I have learned in life is that –where the opposite sex is concerned—the unattainable is not necessarily as unattainable as one might think. Here the SAS motto—He Who Dares Wins—is worth considering.