THOUGHTS OF A WAR BABY

WE ARE AT WAR—BUT WE ARE LARGELY IGNORING THAT FACT.

WE ARE ALSO MAKING ALMOST NO ATTEMPT TO TRULY UNDERSTAND OUR ENEMIES. WE SEEM TO BE CONTENT WITH DEMONIZING THEM.

I try and stay current with national security issues—with a particular focus on small wars, special forces, and terrorism—because they have been an interest of mine for virtually all my sentient life.

Being born in May 1944—which makes me very much a War Baby—may have something to do with it. Hearing stories of the war—still fresh in everybody’s minds as I grew—had a great deal more. People didn’t talk much about actual combat (though that changed as I grew older). More typically, a story would be about wartime privations, or a narrow escape during the bombing—and rationing and the black market were ever discussed. This was scarcely surprising because they still continued. In fact, rationing didn’t end in the UK until the Fifties.

You may well wonder why, since were were Irish, we were in London. Well, the Irish have been going to Britain for decades to find work. In this case my mother moved to London to find excitement. She was bored stiff in neutral Ireland. Wartime London meant night-life, parties and men—in reverse order. There were men there of every race, type, size, and uniform—and mother made the most of it—though she had a bias towards Middle Europeans and the aristocracy. In fact, her third marriage—decades later—was to a Polish count.

Based upon her needs, she had a very good war and I was one of the results. A little bombing didn’t phase her in the least. It just added to the drama—and mother loved drama—and its associated histrionics—more than anyone else I have ever encountered. Life at home was chronically insecure and emotionally turbulent at best—and frequently frightening—but rarely dull.

She also did her bit to defeat Hitler by serving as a radar operator before she became pregnant with me. She was always very proud of having served in the WRAF (Women’s Royal Air Force) and bought me an RAF tie when I was about nine on the strength of it.

Believe it or not—I’m still incredulous when I think back—former RAF Types regularly accosted me thereafter—sometimes angrily—complaining I was not allowed to wear the tie because I hadn’t served. Rather hard to have served when you are too young to shave. They tended to mellow when I explained—or if mother appeared on the scene. She was attractive and verbally formidable (something of an understatement).

In those days, we lived near London and signs of the bombing—normally shattered buildings—were everywhere. A building would look fine from one angle and then you would turn a corner and see a complete wall blown out and all the interiors revealed. Sometimes dishes were still on the table. As a child, I found this fascinating—and disturbing. I have been both blessed and cursed with a vivid imagination and I could imagine what it must have been like when the bomb had exploded.

Many of the bombs were incendiaries because in proportion to their weight and size they could inflict even more damage though fire than explosive devices. An incendiary bomb could weigh as little as a couple of pounds (roughly a kilo) as opposed to 250 pounds for a small explosive bomb. A single German HE-111 bomber could carry 1,152 incendiary bombs. London’s Blitz was not a minor assault.

My grandmother acquired a legendary reputation for neutralizing such devices—normally with a bucket of sand. Given that an incendiary normally contained a small charge of explosives as well—to blow through a roof so that the incendiary could do its work in the more combustible interior-this must have required considerable courage. It was not something she talked about. I heard from others. She was a VAD (an unpaid voluntary nurse) in WW I, and an Air Raid Warden in WW II. After the war, she was an activist helping refugees. Such was Granny’s life—one of endless service to others. I adored her.

Strangely enough, it took the British longer to rebuild than the Germans. The German need was greater, they were more desperate, and almost certainly were better organized. Say what you like about the Germans—and people certainly did, though they are an admirable culture in many ways (with a disconcerting tendency in the past towards aggression)—they know how to make things and to get things done. They also had Ludwig Erhard, the man largely credited with restoring the German economy with such speed. Essentially, he opted for the free market while Britain hung on to price controls. Germany prospered. Britain stagnated.

There were other reasons for Britain’s malaise which were arguably more fundamental. It’s workers weren’t as skilled (German training was, and remains, superior). It had under-invested in manufacturing for decades. It lacked a decent road system (the Germans had built the autobahn system in the Thirties). Its rail system was in disrepair. Class divisions were rife. Socialism was being tried out for the first time and no one knew quite how to do it. There were shortages of just about everything—something almost impossible to imagine in today’s U.S. consumer-driven world. People then re-used envelopes and saved paper, string, and pieces of cloth. Anything which could be re-used was.

London hadn’t been as badly damaged as Berlin, but the British were exhausted, deprived, run-down, and in reaction. They had been at war for six years and it had been a close run thing. The British War Effort been even more total than the German. London had been subjected to two Blitzes. The first had consisted of conventional bombing by aircraft and was really an exercise in frustration because Germany couldn’t secure the necessary air dominance to invade. The Battle of Britain determined that.

The second Blitz started shortly after I was born (in fact, while in my cot, I was told I was showered with broken glass from a nearby blast on one occasion, but was unscathed) and consisted virtually entirely of missiles—nearly 10,000 in all. That is a frightening quantity of explosives—and they were delivered over only a few months. Fortunately, they were comparatively slow so the British became very good at shooting them down. Fighter pilots also learned to insert a wing-tip under the missile wing, bank hard—and thus tip the weapon out of control to crash into the sea or the countryside.

This put the fighter, itself, at risk of crashing, or being blown to pieces. A V-1 carried nearly a ton of Amatol-39 explosive. The pilots displayed astonishing courage.

They, the V-1 rockets, popularly known as ‘Doodlebugs’) made a distinctive noise. This was a characteristic of their pulse jet engines. Then the motor would cut out, and there would be brief seconds of terrifying silence before a massive explosion. If it had been heading your way, you were just plain out of luck.

Doodlebugs, though equipped with a guidance system, were highly inaccurate, but London was a vast urban sprawl, so it wasn’t hard to hit something—which often meant somebody—typically a civilian, often a complete family, though not the children. By and large, children were evacuated, and sent to stay somewhere perceived to be safer. Both parents and children hated the separation, but at least the children lived.

Why wasn’t I evacuated? Now I think about it, I have no idea. I guess I was too small. I don’t think babies who hadn’t been weaned were evacuated. We had to take our chances.

Later in the campaign, the supersonic V-2s were introduced. They were genuine long-range ballistic missiles, and were faster and much harder to shoot down or intercept. The Germans launched over 3,000 of them. This was missile war on a considerable scale, conducted even as Germany itself was being defeated.

Later in the campaign, the supersonic V-2s were introduced. They were genuine long-range ballistic missiles, and were faster and much harder to shoot down or intercept. The Germans launched over 3,000 of them. This was missile war on a considerable scale, conducted even as Germany itself was being defeated.

In fact, we tend to forget that Nazi Germany retained considerable military capability right up to the time it surrendered. It just lost the will to fight on.

After the war, the V-2 went on to become the basis of the entire U.S. missile program.

About 30,000 Londoners were killed in the first blitz—and 50,000 injured. I don’t have the figures to hand for the second Blitz—but they were considerable. The totality roughly equated to the U.S. casualties sustained in the Vietnam War, but the impact in the UK was greater because the majority of the dead and injured were concentrated in London.

Britain didn’t stop being at war when WW II ended. It still had an empire—more a burden than a benefit—and for much of the next couple of decades, Britain was at war with someone somewhere as various parts of the empire fought for independence. Virtually all the campaigns were fascinating as far as I was concerned, and I learned a great deal from them. Many are largely forgotten now—more is the pity—because a great deal can be gleaned from them still. In fact, all things being considered, the British did remarkably well with small numbers of well trained troops operating in a wide variety of environments—and most were conscripts at that.

I recall combat—after WW II was over—in Indo-China (the British were there too briefly), India, Greece, Malaya, Palestine, Egypt, Cyprus, Kenya, Yemen, Indonesia, Oman—and, of course, Northern Ireland. I doubt that list is complete.

One of my marketing colleagues in United Biscuits (my first corporate job in marketing) had been an infantry officer in Malaya, spending days on end in the jungle hunting communist terrorists.

When I asked him what it was like, he said it was terrifying, but though he was city born and bred, he’d got used to it, and they had actually caught and killed a few terrorists even though most of their forays were abortive. He had carried a Sten gun on the grounds that if he bumped into a hostile—and visibility in the jungle was minimal—he wanted to be able to put rounds down-range faster than his opponent.

When I asked him what it was like, he said it was terrifying, but though he was city born and bred, he’d got used to it, and they had actually caught and killed a few terrorists even though most of their forays were abortive. He had carried a Sten gun on the grounds that if he bumped into a hostile—and visibility in the jungle was minimal—he wanted to be able to put rounds down-range faster than his opponent.

A Sten is a cheap but effective British 9mm submachine gun. The magazine protrudes from the left side. This looks odd, but makes re-loading when lying flat, under cover, considerably easier. If you are left handed—the Sten is not for you.

My boss, when I worked in Doyle, Dane, Bernabach Advertising in London, had been a Pathfinder in WW II. He had flown the remarkable all wood Mosquito in advance of bombers to mark where bombing was to take place.

My boss, when I worked in Doyle, Dane, Bernabach Advertising in London, had been a Pathfinder in WW II. He had flown the remarkable all wood Mosquito in advance of bombers to mark where bombing was to take place.

The Mosquito airframe was constructed entirely of wood because of the metal shortage in Britain during WW II. It was a decidedly counter-intuitive concept which worked brilliantly in a wide variety of roles—from precision bomber to fighter—and it was also one of the fastest aircraft for its time. It could achieve well over 400 mph and was powered by two Rolls Royce Merlin engines—the same engine as used in the Spitfire. Nearly 8,000 were made in the end.

The British, when they put their minds to it, may be less well trained and organized than the Germans, but they are capable of astonishing ingenuity. The Mosquito and radar are but two military examples. Consider Alan Turing and Bletchely Park or the numerous inventions of Barnes Wallis (best known for the Dam Busters). There is something about that damp little island—which really had no business being strong enough to create an empire—which promotes innovation and creativity. What is it? I have absolutely no idea unless it is an imperative to escape from the weather.

Being Anglo-Irish—a member of the land-owning class that used to rule Ireland until independence in 1922 (so very much aligned with British interests) I was decidedly conflicted by all this. On the one hand I went to a British public school where I was actually being formally trained to serve in the British Army—we wore British Army uniforms and trained twice a week. On the other hand, I was Irish—liked the idea of Ireland being independent—and, when I thought about it, could see no good reason why the various countries involved, should not have their independence as well.

In practice, they have all achieved just that. All of those small, tragic, colonial wars were unnecessary.

Either way, I followed virtually all the campaigns in as much detail as I could—which, in turn led to my having great interest in the French War in Algeria and the U.S. in Vietnam. My interest in the Algerian conflict led me to track down the French Foreign Legion in Corsica and spend some time with them—then I went to Cyprus to experience the Greek-Turkish confrontation which nearly got me killed.

That happened on several occasions—particularly in Northern Ireland. I am not particularly brave and tried not to be excessively foolhardy, but when you put yourself if harm’s way—albeit for such a worthy cause as researching a book—a bullet doesn’t much care whether you are a writer or not. Combat photographers tend to think they won’t be shot at as well. We are inclined to feel that because we are merely observers we will be safe. The other side tends not to care who or what you are. As far as they are concerned you have a simple designation. You are a target.

In 1969, I didn’t have to go anywhere to experience terrorism. The IRA started up—yet again—and Northern Ireland settled down to 30 years of bombings and shootings. Given the small population of a little over a million, the carnage was considerable. Scale it proportionate to the U.S. population and deaths would equate to around 100,000, and the injured to a multiple of that—and practically all in several relatively compact geographic areas..

Note that length of time. Terrorist campaigns typically last for long periods, so if you are going to engage in counter-terrorism, you had better settle in for the long haul—with associated costs in blood and treasure. This doesn’t seem to suit the American mentality.

I could now, so to speak, commute to the war. In fact, sometimes commuting was not necessary. The action came south of the border—and, sometimes I went to it. Terrorism was rife in the Seventies—though not in the U.S. I doubted that would last.

By complete coincidence, I went to Rome to have a delightful romantic interlude with a woman called Maria some little time after Aldo Moro, Italy’s former prime minister, had been kidnapped by the Red Brigade. He was still missing when I arrived. Unbelievably, the authorities decided to search the whole city, building by building (which they actually did—to no avail), and road blocks manned by nervous cops carrying submachine-guns were everywhere.

In fact, the tension was extraordinary. By this time, the violence in Northern Ireland was such an accepted occurrence that people took it in their stride. Terrorism and the day to day activities of life coexisted. Armed troops patrolled the streets—heads constantly turning as they scanned for snipers—while people did their grocery shopping or walked their dogs. This juxtaposing of violence and the mundane was bizarre, but accepted as normal—because that is exactly what it was.

Nonetheless, the fact that a society can go about its business against a background of terrorist violence should not be confused with terrorism having no effect. It was politically divisive, stressful, seriously undermined the economy, and costly in blood and treasure

It spanned 30 years in Northern Ireland—more than a generation. Its effects will be felt indefinitely. Trust has been destroyed.

In contrast, though there had been some incidents, terrorism was still fairly new as far as the Italians were concerned—and the cops in Rome were jumpy. The bloody kidnapping of a former prime minister was in a league of its own. They were not unaffected by the fact that when Moro was kidnapped, all of his bodyguards had been shot to death. Their unspoken question was: Who is going to be next?

The police clearly thought it was likely to be one of them—and weren’t taking any chances. I was much more concerned that I might be shot by accident than by any terrorist. Safety catches off, twitchy fingers, and tired nervous cops do not inspire confidence. We had one particular encounter at a roadblock which came very close to the edge.

We didn’t have long to wait to find out who was going to be next to die..

As luck would have it, I was nearby when Moro’s body was found. I heard the news from an actor called David Jannssen (best known for The Fugitive) who was filming a TV adaption of the Irving Wallace book, The Word, in Rome at the time. He has a very distinctive voice. I didn’t know him. This was pure happenstance.

As luck would have it, I was nearby when Moro’s body was found. I heard the news from an actor called David Jannssen (best known for The Fugitive) who was filming a TV adaption of the Irving Wallace book, The Word, in Rome at the time. He has a very distinctive voice. I didn’t know him. This was pure happenstance.

His crew were eating in the same restaurant I was—it was near the Pantheon—and he came up and said: “They’ve found him. He is just up there.”

We knew, without being told, who ‘he’ was.

I wen to look and there he, Aldo Moro, was—a bundle in the back of a vehicle. He had been shot in the head. The year was 1978.

I find military matters and terrorism fascinating to study, but the brutal reality of the end result turns my stomach. I felt very sad when I looked at Moro’s body—much as I felt when I found the hanging body which led to my writing Games Of The Hangman. In the latter case, I caught the upper half of the corpse after it was cut down, and was profoundly moved. As I held his torso in my arms—and with blood and mucous coming out of his mouth he was a pretty grim sight—I wanted to hug him, and bring him back to life again. I both study and write about violence—and I have both experienced violence and inflicted it on occasions—but I am not a violent man. Compassion tends to dominate my feelings. Violence is ugly. It is strange, indeed, that it plays such a major role in entertainment. I find it equally strange that even though I am conflicted, I research, read, and write about it so much.

Where terrorism and its consequences are concerned, the most bizarre sight I ever witnessed in Ireland—and there was considerable competition—was watching a British Army helicopter resupply a heavily fortified police station on the border. The IRA, though comparatively few in number, had still made the roads in the area too dangerous for British troops to use. Their weapon of choice was the IED. In the case of paved roads, it was frequently concealed in a culvert so was often referred to as a ‘culvert bomb.’

My point? This wasn’t happening in the Vietnam War or in some movie. This was happening in a modern, developed, Western economy—where I just happened to live. It was surreal.---but the evidence of my own eyes was undeniable. I was more affected by that sight than just about anything else.

You may well ask why the U.S. didn’t learn more from the many irregular wars that have taken place since WW II. All I can say is that we seem to be remarkably reluctant to either learn from abroad, or master our own history. Again and again we pay the price of such ignorance.

A classic example of this concerned our failure to factor in the predictable threats from either RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenades) or IEDs. Both of these were serious threats as far back as the Vietnam War—so we are talking the Sixties—yet we bought the unarmored Humvee and later the flat-bottomed wheeled Stryker for tactical mobility.

The Stryker was fitted with SLAT armor (a cage designed to pre-detonate RPGs) at the last minute to combat RPGs, but nothing was done about the flat hull of the Stryker until about 2011. The point here is that the South Africans had substantially ameliorated the IED problem by introducing armored vehicles equipped with V shaped hulls back in the Seventies.

In the Nineties, I decided the U.S. Army would be the backdrop for a series of books so initially spent time with the 82nd Airborne. Dave Petraeus was a colonel then—and the brigade commander of the unit I was assigned to. He went on, as you will know, to become a four star general and to command Iraq while the surge was being implemented. Then he took over in Afghanistan. After that came the CIA.

I was very sorry when I heard he had resigned. He’s a controversial man who is frequently accused of being excessively ambitious. I have no idea of the truth of that. I happen to like him personally and regard him as exceptionally able.

That visit to the 82nd proved so worthwhile that I returned a couple of years later to research the entire XVIII Airborne Corps—which turned out to be a more substantial task than I had realized.

A corps is an army in itself in that it contains the full spectrum of capabilities available to an army—infantry, armor, engineers, aviation, logistics, medical, intelligence, and so on. A corps typically contains a number of divisions and can vary substantially in size. Since a division typically numbers 10-15,000, a corps can contain 50,000 soldiers or more. Add in the civilian workforce and families, and you are up to the size of a small city—where a substantial proportion has to be prepared to deploy globally and fight pretty much anywhere in the world.

Commanding such a unit is an awesome responsibility.

The XVIII Airborne Corps contained two airborne divisions, one light division, and—oddly enough—the heavy 3rd Infantry Division (Mechanized) which contained tanks and infantry fighting vehicles.

One exception to the full spectrum principle, is that a U.S. corps typically doesn’t contain Special Forces—as such—though they can be attached to it, and frequently are. Special Forces have their own command, and their own ways of doing things though the Big Army (or Green Army) tries to rein them in. There is a profound cultural clash between the two. The Big Army tends towards centralized authoritarianism and deploys in large numbers. Special Forces are highly trained and empowered soldiers who operate in small numbers with considerable autonomy.

I will confess a strong bias in favor of special forces (the small ‘s’ means special forces in general as opposed to just U.S. Special Forces) and their mindset. They tend to fight smarter and be disproportionately effective (though there are limits to what they can do as matters stand). My interest in them started in school. The founder of Britain’s legendary SAS (Special Air Service) David Stirling (see photo), had been a pupil there so we were all familiar with his story, and many past Ampleforth pupils went on to join ’The Regiment.’ One, Captain Robert Nairac, was kidnapped, tortured, and shot to death by the IRA under circumstances which I very nearly duplicated. I was lucky enough to get away. He didn’t. His body has never been found.

I will confess a strong bias in favor of special forces (the small ‘s’ means special forces in general as opposed to just U.S. Special Forces) and their mindset. They tend to fight smarter and be disproportionately effective (though there are limits to what they can do as matters stand). My interest in them started in school. The founder of Britain’s legendary SAS (Special Air Service) David Stirling (see photo), had been a pupil there so we were all familiar with his story, and many past Ampleforth pupils went on to join ’The Regiment.’ One, Captain Robert Nairac, was kidnapped, tortured, and shot to death by the IRA under circumstances which I very nearly duplicated. I was lucky enough to get away. He didn’t. His body has never been found.

Funnily enough, apart from going to the same schools, Gilling Castle and Ampleforth College, we both have French associations. One of my ancestors, Benjamin Lentaigne, came from Normandy. Nairac’s ancestor—and his name—came from the Gironde. He also had Irish ancestors.

All my thrillers feature special forces—particularly an Irish unit known as ‘The Rangers.’ Strangely enough, I invented them at about the same time the real unit, called The Ranger Wing—was actually created. Later I was invited to visit with them—which was quite an honor. They prefer to keep a low profile, as do the SAS.

All my thrillers feature special forces—particularly an Irish unit known as ‘The Rangers.’ Strangely enough, I invented them at about the same time the real unit, called The Ranger Wing—was actually created. Later I was invited to visit with them—which was quite an honor. They prefer to keep a low profile, as do the SAS.

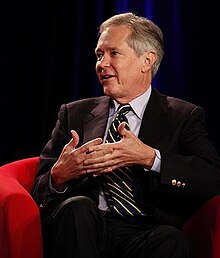

In fact, I never made it to the 10th Mountain Division. That apart, it was a thoroughly rewarding experience—and it was how I met General Jack Keane, then the commanding general of the XVIII Airborne corps—who was to go on to become the Vice Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army—effectively the man who runs it on a day to day basis.

The Vice Chief is called ‘the Vice’—a marvelously evocative title. The Vice is the man who gets things done. He also happens to be Dave Petraeus’s friend and mentor. The airborne world is nothing if not connected.

Jack Keane, an intelligent, imposing, ambitious man with a forthright style (who is decidedly more complex than he seems), impressed me greatly and we took to each other. In fact, it was thanks to him that I ended up spending time with the 101st Airborne (Air Assault) Division, and flying in an Apache AH-64 Attack helicopter—both by day and by night.

That exposure to Army aviation not only taught me a great deal, but changed my life. Through it I met Chief Warrant Office 4 Tim Roderick—now one of my closest friends, colleague, and much else besides. He is also a walking encyclopedia of military matters to a degree that is just plain astonishing. Here, I don’t just mean facts. I mean history, strategy, tactics, techniques, and procedures. Tim is the most professional military man I know—which is saying quite a lot, because I know some exceptional warriors.

Warrants are the problem solvers of the Army, and, generally speaking, are specialists. It’s an interesting rank.

Rank is a subject unto itself—and is given too much importance in the Army. On the one hand, history has proved it to be necessary where the military are concerned. On the other hand, all too often rank is abused and used in an excessively authoritarian manner. The most disconcerting aspect is the implicit assumption that the person with the higher rank automatically knows more. A fundamental difference with special forces is that they place less emphasis on rank and much more on proven competence—and special forces troopers are encouraged to speak up. In fact, the most senior special forces soldier in rank may not command on a particular mission. The requirements of the mission determine that.

The overall effect of empowering soldiers is to make them better soldiers. I also question whether rank and pay should associated to the extent they are. Sometimes a soldier is so good and comfortable in a role he or she should be left there, but still be rewarded with higher pay. There are certain key roles where this is particularly applicable—such as company commander. As a general rule, U.S. Army officers don’t get enough command experience. It takes time, training and practice to produce seasoned commanders. In fact, you can say the same about soldiering in general—veterans take lower casualties for good reasons—but it is particularly relevant where certain command positions are involved.

Concurrent with familiarizing myself with the U.S. Army, I also researched the NYPD, the FBI, and the Congressional Task F0rce on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare. Apart from my innate interest, my feeling was that if I was to write thrillers, I should be as familiar with the security milieu as possible, and in as much depth as I was intellectually capable of. It turned out to be a fairly gargantuan task—and continues to be so. National security encompasses a very great deal—and, despite its innate conservatism, evolves constantly. I endeavor to keep track of it holistically—partly because of time limitations, and partly because that is the way I think naturally.

Combat has mostly evolved around weapons and systems which would still—broadly speaking—be familiar to the soldiers of WW II, but we are now transitioning to a level of combat technology which demands a whole new mindset and level of expertise to grasp. Such technology includes computerization in general, drones, robots, the extraordinary accuracy of modern PGMs (Precision Guided Missiles), lasers, cyber war—and the sheer pace of technological change. Whether our current structure are geared to handle that is open to some doubt.

I find it hard to realize that much of my hands-on field exposure to the Army and National Security in general started to happen nearly 20 years ago now. Given that my interest in this area commenced decades before that, I have been immersed in this fascinating but dangerous world for a very long time. Keeping up with it all in detail is impossible, but I try and retain a sense of things, of how the pieces fit together, and then zero in where necessary.

My greatest interest is the Army. I am a critic at times—which the Army doesn’t like—but I hope a constructive critic. It’s hard to feel affection for an institution, but there is a great deal of truth in the saying, “You’ve got to love soldiers.” The camaraderie is very real. Time spent roughing it with troops in the field is time well spent.

I first heard that remark while spending time with 3rd ID—the tank division—at Fort Irwin in the Mojave Desert. They managed to lose me in an impact zone (supposedly full of unexploded munitions) at night, gas my driver badly, gas me unpleasantly, forget water (in the desert) forget to feed me, issue us with a faulty radio—and much else besides—but then General Keane arrived (dramatically, by helicopter—I was on a hill and it seemed to rise out of the ground) and he allocated a BG, Dale Nelson, to look after me—and he was the source of the saying.

Keane also lent me his binoculars—a gesture that was as much symbolic as practical. I then pushed my luck and asked for a helicopter. I wanted to see Fort Irwin from the air.

Keane paused at this one—gave me a long hard look—and then granted my request.

Let me tell you having my very own Blackhawk for a while was an absolute blast—though I was somewhat disconcerted when I found they were firing 155mm artillery over us. Just suppose they got the elevation wrong. Having a vivid imagination can be a mixed blessing.

Still, what an appropriate way for a thriller writer to do. It would do wonders fro my sales!

A BG is a brigadier general—a one star. I always think of BGs as ‘Baby Generals’—but the operative word is ‘general.’ The lust for a star drives the senior officer corps.

Generals like being called “General,” much as a penis—or a clitoris for that matter—likes being stroked (a lot—and they stand more erect) but it creates an imbalance in the relationship since I’m normally called by my first name—which prefer (Ireland is a first-name culture). Also I am now older than most serving generals—and was when I made the change. Anyway, I thought about this for a while and decided I would address generals by their first name. They flinch occasionally, but mostly it has worked. If I was in the chain of command—an entirely different situation—I would call a general by his rank.

Looked after by a BG or not (and Dale was pretty good), they managed to injure me on the last day as we tried to drive cross the desert at far too high a speed in a HUMVEE (and neither door nor seat belt). After we hit a bump, my badly gassed driver—who was sitting in the rear—was flung up, and forward, and crashed through the windscreen. onto the hook Fortunately, there was no glass in it. Still, it was a good thing he was wearing his helmet. I spent two weeks in pain trying to get a thigh muscle I had strained from not looking like a protruding baseball.

But, as we writers like to say, it’s all material. I loved it. My epiphany, where the ordinary soldier is concerned, took place when I was in a Blackhawk watching young scared troopers rappel to the ground as part of graduating from the Airborne Assault course. We were 100 feet up so a fall would kill—and not only were the doors wide open but so was an aperture in the floor. I felt decidedly insecure.

Though I had talked my way onto the aircraft for the experience, I’m terrified of heights. Watching those visibly nervous kids master their fears was an inspiration—and a lesson that courage is infectious. I even started hanging out the open door to take photographs (a wonder in itself if you knew how badly I am affected by vertigo).

How do I achieve such access? I’m a great believer in the Letter of Introduction. I received my very first one from a journalist friend of the family back in my teens—it was from the Dublin Evening Mail (now defunct) and progressed from there. Essentially it is a matter of asking, establishing credibility through such letters, patience and persistence. It also helps if you have a book to show (though that is not essential). I give virtually everyone who helps me a book. Luck is also a factor. My first U.S. editor, Rosemarie Morse, had a friend who was dating a former NYPD cop called Dennis Martin who came from a family of cops. They asked to meet me and we became friends. Through him I not only had a lot of fun but connected with Jim Fox, then head of the FBI in New York. And so it progressed.

Jim Fox was a remarkable man and great company—empathetic, shrewd, thoughtful. and extremely amusing. He had spent much of his distinguished FBI career in intelligence—both as a spy hunter and as a case officer managing spies. Among his other talents he spoke Mandarin. He built the case that convicted John Gotti and headed the 1993 World Center investigation.

Aged 59, he died far too young. I went to his retirement party which was attended by anybody who was anybody. Governor Cuomo was there and so was Mayor Giuliani (whom I met—and did not warm to). What I remember most—with some wry amusement—was that while I was sitting beside NYPD’s Chief of Detectives, I had my camera stolen.

In the late Nineties, I became involved with a group of military thinkers and reformers of world class caliber who have taught me more than I can say. This loose group is anchored by Tom Christie’s Fort Myer Wednesday meeting, but includes many who aren’t necessarily physically present but who make a major contribution to military thinking. The distinguished journalist, James Fallows used to be an attendee. That Fort Myer group is much more extensive and influential than one might think—and it is still going strong.

I rate Jim Fallows very highly. He is well informed, measured, writes beautifully—and is the epitome of a thoroughly decent human being. He also interviewed me at one stage and offered a flight in his aircraft as an inducement. I was happy to talk without one, and, as it happens, we did the interview on the phone. Nonetheless, he flew down subsequently and gave myself and my kids a flight in his Cirrus—and afterwards we had a meal together and talked at some length.

I rate Jim Fallows very highly. He is well informed, measured, writes beautifully—and is the epitome of a thoroughly decent human being. He also interviewed me at one stage and offered a flight in his aircraft as an inducement. I was happy to talk without one, and, as it happens, we did the interview on the phone. Nonetheless, he flew down subsequently and gave myself and my kids a flight in his Cirrus—and afterwards we had a meal together and talked at some length.

This is a man who remembers his promises. We have many shared interests including defense matters, computers, and aviation. You can read his work in The Atlantic—and elsewhere. He has been there since dinosaurs roamed the earth.

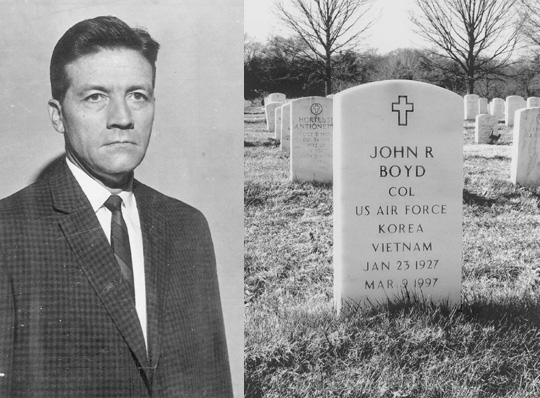

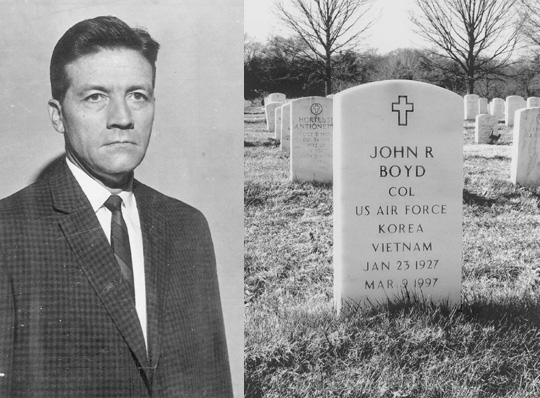

The group was started by John Boyd of OODA loop fame. ‘Observe; Orient; Decide; Act.’ He is worth reading about. Check out books by Robert Coram, Grant Hammond, and Chet Richards. Many regard him as one of the most significant military thinkers in years. Unfortunately, his ideas were primarily presented through briefings. He didn’t write any books or even position papers (as far as I know). Nonetheless, his flame is kept alive and, if anything, his stock seems to be increasing.

By all accounts, Boyd was masterly at getting things done—a near impossibility in the bureaucracy that is the Pentagon. My favorite story about him concerns his making a point to a recalcitrant general by poking him repeatedly with his smoldering cigar—to the extent that he finally set fire to the general’s shirt. But typically Boyd outmaneuvered his opposition. A brilliant fighter pilot, he was known as Forty Second Boyd because that was all the time it took for him to get on your tail—even if he had started in front of you.

Are the ideas of the reformers always listened to? Sadly they are not. The Pentagon—generally called ‘The Building’ by the cognoscenti—and shorthand for the Department of Defense—like many large and powerful institutions, is not overly fond of listening, and lacks a mechanism for doing so (a serious weakness of many institutions). Being both powerful and authoritarian, it is also arrogant.

A strange feature of the Pentagon, and its component services, is that although they all have Public Affairs Departments—and here I am speaking from considerable experience—the orientation of such departments is almost entirely propagandist and defensive. They seem to think that they exist solely to put across the party line to to defend their organizations against criticism (and that lying in pursuit of a higher goal is justified). The fact that they could play an invaluable role by engaging in genuine two-way communication seems to escape them. If you want a classic example of that, consider the Tillman case where every effort was made to disguise the fact that he had been shot by friendly fire. The trouble is that when public affairs lie so egregiously they destroy credibility.

Mostly, the Pentagon does what it wants its way—and largely ignores criticism. Nominally, Congress has oversight, but so many committees, subcommittees, and panels are now involved, the end result is minimal effective supervision. On top of that, the Pentagon cannot be audited. It features too many incompatible accounting systems for mere mortals to make sense of it all. In effect, it is unaccountable.

Is this by accident or design? One can but speculate.

The Pentagon is where the military interface with money, politics, power, ambition, and bureaucracy—and the result is pretty horrendous and badly needs root and branch reform. It is careerist, corrupt, inefficient, inflexible, over-staffed, vastly over-costly, and puts far more effort into inter-service rivalry than war-fighting. The auditing issue is only one of its problems. Its acquisition process is a nightmare—and apart from costing too much, takes far too long. This is particularly concerning given the pace of technological change. If you take a couple of decades to produce a weapons system, it tends to be obsolete long before it is accepted for service.

This inability to be audited makes the Department of Defense in permanent violation of Federal law. We go on shoveling money in anyway. We can’t very well shut down National Defense even if we don’t quite know where the money goes—or whether we get value for it (we don’t).

If you want to get a sense of whether we get value or not, compare the National Security budgets of the U.S. and Israel. Israel doesn’t have the same global commitments we do—and it doesn’t have to travel far to fight—but, even so, it is a nuclear power which is able to field a large and sophisticated military force when required. Its research and development is also cutting edge and superior to ours in some areas (arguably more than a few)

What are the comparable figures?

Note that National Security includes not defense but related expenditure on such matters as veterans.

Both figures are a little rough, but no matter how you look at it, Israel spends a tiny fraction of what we do.—and gets much more bang for the buck. The contrast is so dramatic, you have to wonder. Could we learn anything from the Israelis?

A very great deal.

Just for starters, they save a fortune by fielding only a relatively small permanent military but having a vast militia. Also, they don’t suffer from rank inflation the way we do. But, it is more than than that. They just plain buy better—and faster.

In 2001/2 I actually worked for the Pentagon for a while as a consultant to General Jack Keane (see photo) when he was Vice. That gave me the kind of access a writer like myself would practically kill for—fortunately not required in this case—and led me beyond thriller writing to consulting, and then to my actually expressing opinions on weapons systems and strategy.

In 2001/2 I actually worked for the Pentagon for a while as a consultant to General Jack Keane (see photo) when he was Vice. That gave me the kind of access a writer like myself would practically kill for—fortunately not required in this case—and led me beyond thriller writing to consulting, and then to my actually expressing opinions on weapons systems and strategy.

As it happens, I became very deeply involved—probably more so than a writer should. On the other hand, the cause was worthy. The details can await my memoirs. I paid a heavy price for getting involved—but I would do it again. Sometimes you have to do what you feel is the right thing regardless of the price. Sometimes the hard part is knowing what the right thing is. Commenting on weapons and weapons systems brings you up against vested interests of enormous power and influence. Billions of dollars are involved. It is dangerous ground.

I completed my Pentagon phase with so many knives in my back, it resembled a pin-cushion. Still, traditional publishing is even more treacherous so I wasn’t excessively disturbed. Though few would speak out publicly, I also had numerous supporters.

My priority in this particular case wasn’t my career. It was the soldier at the sharp end. I had met enough during my time with various units to hold them in high regard. Were we buying them the right equipment? I thought not—and said so.

At this stage, do I consider myself a military expert?

As I have written before, I am reluctant to use that word. Experts normally know a great deal about a specific area. I have accumulated a unique body of broad based experience which means I understand how the pieces fit together better than most, but probably don’t have the depth of expertise in some areas that an expert should. Here, I don’t intend to be modest—merely factual. But, subject to that caveat, I am remarkably experienced, well informed, and insightful—and am eminently qualified to comment on defense issues across a broad range of sectors. I am, without question, a military thinker.

Are my ideas original? Some may be—but I make no such claims—nor is that my goal. Though I do have my own ideas, here, as with the economy, I’m much more concerned with determining what works—and communicating it effectively.

If my ego needs a work-out, I have my novels to give it satisfaction. Where both military matters and the economy are concerned, I’m a pragmatist.

My standard is not—is it original? My standard is whether it works. Claiming credit for an idea has a tendency to slow the adoption of the idea in question which is not what you want when lives are at stake—whether financially or physically.

Where my novels are involved, I’m delighted to be thought original, entertaining (or whatever) and to accept whatever accolades are going. Regretfully, I haven’t managed to eliminate my ego entirely—because it has a tendency to distort one’s judgment—but I guess you could say I have compartmentalized it.

What am I doing right now with this expertise?

-

Editing a non-fiction book on the future of the U.S. Army

-

Writing a novel based around the Army

-

Commenting as and when in this blog and elsewhere.

-

Developing some additional ideas—which, for the moment shall be nameless.

-

Carrying out a great deal of additional research.

-

Worrying about the lack of intellectual honesty, integrity, and depth where defense is concerned.

I am greatly concerned about the direction of our national defense.

-

We have evolved the most expensive way of war the world has ever known. We behave as if cost was no object but ignore that we have other urgent commitments.

-

We are spending an excessive amount on defense without having a clear national strategy focused upon what we want to achieve. Appreciate that the Defense Budget represents only part of what we spend on National Security. Our total expenditure here exceeds $1 trillion.

-

We are still borrowing money to make war. This is the most acceptable method in the short term politically, but it means we are going to end up paying interest on the interest on the money we are borrowing. This is going to cripple the budget downstream—and we have other urgent needs.

-

We have set ourselves up as a de facto global police force to the point where we are grossly overextended with bases all over the world—and without having the resources to fulfill such a global commitment. At the same time we haven’t yet mastered the art of deploying as speedily and effectively as we need to. These are complex issues because, on the face of it, foreign bases seem an advantage (and having a limited number certainly is). However, when you have as many as we do right now (roughly a 1,000 including about 250 golf courses) they have a number of undesirable side effects: they are costly to operate both financially and in terms of human resources; they threaten our enemies to the point where an arms race develops; they dissipate effort; they cause rank inflation because a senior officer is needed to command each base; their sheer number means that the forces in any one individual base are strong enough for any anticipated mission. Overall, I would argue in favor of considerably fewer bases but a much enhanced and faster expeditionary capability. Tom White, then the Secretary Army, once told me we had so many bases roughly 10 percent of our military manpower was in transit to and from them at any one time—and thus could not be used.

-

We cannot account for our expenditures. We already know that every time we occupy a country, corruption goes through the roof. Why do we assume it is limited to over there? There are serious grounds to believe it is endemic here. However, the bottom line is that we don’t know, and we should.

-

We continue to have serious problems with intelligence—despite the vast sums we spend on it. We still seem to be overly focused on target sets—things we can count—and weak on understanding cultures, beliefs, and intentions (both stated and covert). We have placed ourselves in a state of permanent war without making any serious effort to understand our enemies. This is an extraordinarily serious omission. These are very smart people who may well be able to lay their hands on nuclear weapons sooner rather than later. The homeland has remained largely unscathed since 9/11 but I can see no particular reason why that should continue. Yes, internal security has been much improved—but we have also increased the number of our enemies. Further, natural selection has ensured that the survivors are more experienced,capable—and familiar with both our strengths (which they avoid) and weaknesses (which they have leaned to exploit).

-

We make trite announcements such as “Islam is a religion of peace” without knowing what we are talking about. How many of us have really taken the time to be informed of the history, complexities and schisms within Islam? If one thing is absolutely clear it that Islamic Wahabis do not advocate peace. Here it is worth noting that the main backers of the Wahabis are the Saudis who are supposed to be our allies. The reality is that they are both allies and enemies—a complexity we have largely chosen to ignore. Up until recently we have needed their oil—and we sell them vast quantities of military equipment. Concurrently, they fund organizations like ISIS—albeit not normally officially. But this is something Saudi intelligence could largely stop if they wanted to. The Saudi regime is also the antithesis of a democracy. We are allied with a regime whose values are the antithesis of ours.

-

We have evolved a MICC—Military Industrial Congressional Complex—which has now become so powerful, it operates virtually without oversight. Roughly two third of retiring generals are hired by defense contractors. These are the same people who decide what weapons systems should be bought. They are guilty of conflicts of interest on an industrial scale. Such conflicts have become normal to the point of acceptability in the Pentagon.

-

Partly because of the MICC—which has, in effect, monetized, Duty, Honor , Country—careerism is rife. Careerism means putting your career ahead of your mission. Given the example of general after general feathering his own nest to the extent so many do, perhaps the prevalence of careerism should not be a surprise. But is is exceedingly unhealthy. It constitutes a form of moral rot.

-

We are operating our defense establishment as if it was virtually entirely independent of ‘We The People.’ We’ve subcontracted it.

-

Our foreign policy is dominated to excess by oil and defense interests. In reality we have many other interests which deserve much greater considerations. Are we, for instance, under-utilizing our soft power? I would argue that we are.

War is far too serious and disgusting a business to be making it without the full support, commitment, and participation of the American people—who also need to be made aware of the consequences in a much more direct way. We need to know not just our own casualties but who else we are killing and injuring, how, and why.

To be at war without most of us being aware of it, or paying for it, or being touched by it in any way, seems unwise as a minimum—and just plain wrong.

In many ways, we have an exceptionally fine military—and are justifiably proud of it. Yet if you look the results after more than 13 years of war, it is hard to feel sanguine about our achievements. But if there is blame, I doubt it lies with the troops as such. In fact their overall performance has been fairly remarkable. But, subject to some—perhaps many—notable exceptions, I doubt one can say the same about either our policies or senior leadership—both civilian and military. For instance, our strategic focus has been erratic at best. We lost interest in Afghanistan to invade Iraq, and then did much the same in Iraq in order to re-focus on Afghanistan.

The pattern is clear. It is easy enough to get into a conflict but prodigiously hard to end one. We tend to linger. We seem to have scant skill at expeditionary warfare where you mount an assault, teach a lesson, and then got out. It has a much better track record than occupation—and it is less costly by an order of magnitude. It also allows the losers to save face (because they claim victory) which makes it easier to make piece. Occupation is a different thing entirely.

The future for both places scarcely looks encouraging. Iraq is corrupt, fragmented and a significant portion is occupied by ISIS. Afghanistan is corrupt, fragmented, and outside the main urban areas, the Taliban seem to be resurgent.

Yes, we have killed Bin Laden and severely degraded Al Qaeda—but other organizations have sprung up to take their place so we have ended up with rather more enemies than before. Islamic extremism is now rife in numerous countries in Africa for instance—and is proving to be remarkably difficult to contain. Boku Haram, for instance, are proving to be far more resilient than one might suspect.

A good case can be made for a drastic re-think of our National Security. I start from the basis that we need to remain militarily dominant. Restraint should not be confused with weakness—much as the scale of expenditure should be be confused with military effectiveness.

I believe absolutely that we could have a stronger and more effective military at lower cost.

The following are just a few of the question which come to mind.

-

Is our tendency to lead with military power the best way of doing things?

-

Does it really make sense for us to have bases all over the world and to have a military presence in at least half the world’s nations?

-

Are we getting value for money with our National Security dollars

-

Have we given thought to the fact that our military actions promote comparable reactions?

-

Would it be better if our military were more U.S. based but also more deployable?

-

Is the MICC—Military Industrial Congressional Complex—which President Eisenhower warned us about, healthy—and, if not, what are we going to do about it.

-

How do we deal with the problem of careerism?

-

Why have we fought so many wars since 1945—yet either drawn or lost most of them?

-

Should our military be more integrated with the population as a whole—and should we rely more on a militia?

-

Does it make sense to have as many separate military services as we do—which spend a great deal of time and energy fighting each other—and which involve prodigious waste and duplication? For instance, we have three air forces.

-

Why are we allowing the Air Force to buy over 2,000 of the limited, deeply troubled, and vastly expensive F-35?

-

Why are we allowing the Air Force to neglect CAS—Close Air Support—while doing their utmost to scrap the immensely capably and combat proven A-10—which was designed and built specifically for the task?

-

Why doesn’t the Air Force employ much less expensive aircraft for the COIN role?

-

Why did we allow the Air Force to take over the C29J program—originally an Army program—and then scrap it on the back of specious figures? Why did we allow the Air Force to connive in the destruction of 18 similar aircraft given to the Afghanis?

-

Why isn’t the Coast Guard integrated with the Navy?

-

What is the Nayy going to do about the vulnerability of its aircraft carriers to hypersonic missiles?

-

Why is the Navy spending so much on the inadequately armed and protected LCS?

-

Why is the Marine Corps so large in relation to its mission—and what exactly is its mission anyway?

-

Why aren’t the services and Veteran’s Administration records integrated?

-

Why has the Army allowed itself to become so road bound—particularly given the ubiquity of IED’s?

-

Given that PGMs—Precision Guided Missiles—are becoming increasingly common, how is the Army going to fight its armor?

-

Why does the Army continue to tolerate such a huge logistics tail—a major vulnerability in fight?

-

Given the Air Force’s unwillingness to embrace the CAS mission, why doesn’t the Army take it over?

The above list is only a tiny extract of the questions that could, and should, be asked and answered—but somehow we let them fester on.

Why is that? Vested interests have no interest in discussing such matters—they like the status quo. Vested interests include all the players who constitute the MICC—senior military, both serving and retired, and civilian Department of Defense employees. They have powerful weapons on their side including the ability to classify everything. Appreciate also that Congress is part of the MICC. Members of Congress are both bought directly through PAC donations, or kept in line through defense money spent in their districts. Oversight is tough to do when the very people you are supposed to be overseeing are paying you off.

He who pays the piper can get away with most anything—especially where defense contracts are concerned. Is this corruption? Apparently not if everyone does it. As with careerism, it becomes part of the culture.

The media are kept from asking too many questions by the media owners, who want defense advertising money, and by the military who use access as a primary instrument of control. Some media have joined the Dark Side and are members of the MICC. The public as a whole have neither the knowledge nor the interest. Defense think-tanks are largely funded by either the defense industry or the services.

It all adds up to a very good example of how freedom of speech works better in theory than in practice—particularly when the media are muzzled.

That leaves a sprinkling of concerned citizens—many knowledgeable former military or retired DOD employees—who do a commendable job considering their limited resources—and the odd War Baby.

Entirely suitable, when you think about it. You would imagine annual expenditure of over a trillion dollars would command more attention. Hell, it is almost real money.

It’s an odd situation.

VOR words 9,440.

Given that I recently commented that I was going to try to write shorter blogs, you may well wonder at the length of this piece.

So do I!

The answer is that from time to time I tend to feel the need to write at greater length—and this piece seemed to justify it.

I also like to test myself with different lengths from time to time—and this comes into the 5-10,000 word category—what one might consider ’long-form’ journalism. It is the kind of length I like for a serious subject—though decidedly long for a blog.

A third reason is that I’m working up to writing a series of memoirs—and I like to drill down into memory now and then and see what is there. It’s a surprisingly useful exercise.

I hope in 2015 to find a separate location for my longer pieces.

Later in the campaign, the supersonic V-2s were introduced. They were genuine long-range ballistic missiles, and were faster and much harder to shoot down or intercept. The Germans launched over 3,000 of them. This was missile war on a considerable scale, conducted even as Germany itself was being defeated.

Later in the campaign, the supersonic V-2s were introduced. They were genuine long-range ballistic missiles, and were faster and much harder to shoot down or intercept. The Germans launched over 3,000 of them. This was missile war on a considerable scale, conducted even as Germany itself was being defeated. When I asked him what it was like, he said it was terrifying, but though he was city born and bred, he’d got used to it, and they had actually caught and killed a few terrorists even though most of their forays were abortive. He had carried a Sten gun on the grounds that if he bumped into a hostile—and visibility in the jungle was minimal—he wanted to be able to put rounds down-range faster than his opponent.

When I asked him what it was like, he said it was terrifying, but though he was city born and bred, he’d got used to it, and they had actually caught and killed a few terrorists even though most of their forays were abortive. He had carried a Sten gun on the grounds that if he bumped into a hostile—and visibility in the jungle was minimal—he wanted to be able to put rounds down-range faster than his opponent.  My boss, when I worked in Doyle, Dane, Bernabach Advertising in London, had been a Pathfinder in WW II. He had flown the remarkable all wood Mosquito in advance of bombers to mark where bombing was to take place.

My boss, when I worked in Doyle, Dane, Bernabach Advertising in London, had been a Pathfinder in WW II. He had flown the remarkable all wood Mosquito in advance of bombers to mark where bombing was to take place.

As luck would have it, I was nearby when Moro’s body was found. I heard the news from an actor called David Jannssen (best known for The Fugitive) who was filming a TV adaption of the Irving Wallace book, The Word, in Rome at the time. He has a very distinctive voice. I didn’t know him. This was pure happenstance.

As luck would have it, I was nearby when Moro’s body was found. I heard the news from an actor called David Jannssen (best known for The Fugitive) who was filming a TV adaption of the Irving Wallace book, The Word, in Rome at the time. He has a very distinctive voice. I didn’t know him. This was pure happenstance. I will confess a strong bias in favor of special forces (the small ‘s’ means special forces in general as opposed to just U.S. Special Forces) and their mindset. They tend to fight smarter and be disproportionately effective (though there are limits to what they can do as matters stand). My interest in them started in school. The founder of Britain’s legendary SAS (Special Air Service) David Stirling (see photo), had been a pupil there so we were all familiar with his story, and many past Ampleforth pupils went on to join ’The Regiment.’ One, Captain Robert Nairac, was kidnapped, tortured, and shot to death by the IRA under circumstances which I very nearly duplicated. I was lucky enough to get away. He didn’t. His body has never been found.

I will confess a strong bias in favor of special forces (the small ‘s’ means special forces in general as opposed to just U.S. Special Forces) and their mindset. They tend to fight smarter and be disproportionately effective (though there are limits to what they can do as matters stand). My interest in them started in school. The founder of Britain’s legendary SAS (Special Air Service) David Stirling (see photo), had been a pupil there so we were all familiar with his story, and many past Ampleforth pupils went on to join ’The Regiment.’ One, Captain Robert Nairac, was kidnapped, tortured, and shot to death by the IRA under circumstances which I very nearly duplicated. I was lucky enough to get away. He didn’t. His body has never been found.  All my thrillers feature special forces—particularly an Irish unit known as ‘The Rangers.’ Strangely enough, I invented them at about the same time the real unit, called The Ranger Wing—was actually created. Later I was invited to visit with them—which was quite an honor. They prefer to keep a low profile, as do the SAS.

All my thrillers feature special forces—particularly an Irish unit known as ‘The Rangers.’ Strangely enough, I invented them at about the same time the real unit, called The Ranger Wing—was actually created. Later I was invited to visit with them—which was quite an honor. They prefer to keep a low profile, as do the SAS.

I rate Jim Fallows very highly. He is well informed, measured, writes beautifully—and is the epitome of a thoroughly decent human being. He also interviewed me at one stage and offered a flight in his aircraft as an inducement. I was happy to talk without one, and, as it happens, we did the interview on the phone. Nonetheless, he flew down subsequently and gave myself and my kids a flight in his Cirrus—and afterwards we had a meal together and talked at some length.

I rate Jim Fallows very highly. He is well informed, measured, writes beautifully—and is the epitome of a thoroughly decent human being. He also interviewed me at one stage and offered a flight in his aircraft as an inducement. I was happy to talk without one, and, as it happens, we did the interview on the phone. Nonetheless, he flew down subsequently and gave myself and my kids a flight in his Cirrus—and afterwards we had a meal together and talked at some length.

In 2001/2 I actually worked for the Pentagon for a while as a consultant to General Jack Keane (see photo) when he was Vice. That gave me the kind of access a writer like myself would practically kill for—fortunately not required in this case—and led me beyond thriller writing to consulting, and then to my actually expressing opinions on weapons systems and strategy.

In 2001/2 I actually worked for the Pentagon for a while as a consultant to General Jack Keane (see photo) when he was Vice. That gave me the kind of access a writer like myself would practically kill for—fortunately not required in this case—and led me beyond thriller writing to consulting, and then to my actually expressing opinions on weapons systems and strategy.