READ NOT JUST WHAT THEY WRITE—READ WHAT THEY SAY

A MODEST SUGGESTION THAT YOU DIP INTO THE PARIS REVIEW INTERVIEWS OF AUTHORS

Packing continues, and I am beginning to solve some of the trickier problems. It is really not a mammoth operation, but books weigh heavy, and ring-binders in volume can be awkward. Unless packed tightly, the mechanisms can be damaged, and then they are virtually unfixable—and refuse to stand upright.

Packing continues, and I am beginning to solve some of the trickier problems. It is really not a mammoth operation, but books weigh heavy, and ring-binders in volume can be awkward. Unless packed tightly, the mechanisms can be damaged, and then they are virtually unfixable—and refuse to stand upright.

I feel civilization would be greatly advanced if someone developed a robust ring-binder that would stand on its own, and not flop. In Europe, people use lever-arch files—which have only two rings and are generally a standard robust width—and they don’t flop. They are particularly popular in Germany where I doubt they would dare to flop. Germans take administration very seriously. They also—along with the rest of Europe—use a different size of paper (A4 – 8.267” x 11.692”) which is just different enough to be an absolute menace. I confess I prefer the standard U.S. letter size (8.5” x 11”). To me, it just looks better, and such details are important if you spend a considerable time immersed in them.

And don’t suggest either a Kindle or an iPad! In fact most of my files are now electronic, but for certain purposes—like having a backup and editing--I still like paper.

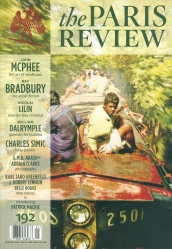

While pondering such mighty thoughts—we authors are serious thinkers—I ran across an article from the admirable www.brainpickings.org featuring extracts from a Paris Review interview with Ray Bradbury. That led me to Google the Paris Review Interviews and to recall how helpful I found them while on my long pilgrimage to become a writer.

They were started by that unorthodox maverick,  George Plimpton, decades ago and he managed to make them sound like frank conversations between friends—which frequently they were, because he knew everybody—and to draw out the personalities of his interviewees. As a consequence, the actual conversations tend to be candid, amusing, provocative, informative and thoroughly entertaining.

George Plimpton, decades ago and he managed to make them sound like frank conversations between friends—which frequently they were, because he knew everybody—and to draw out the personalities of his interviewees. As a consequence, the actual conversations tend to be candid, amusing, provocative, informative and thoroughly entertaining.

Let me quote a short extract from the Ray Bradbury interview to give you the flavor:

INTERVIEWER

Why do you write science fiction?

RAY BRADBURY

Science fiction is the fiction of ideas. Ideas excite me, and as soon as I get excited, the adrenaline gets going and the next thing I know I’m borrowing energy from the ideas themselves. Science fiction is any idea that occurs in the head and doesn’t exist yet, but soon will, and will change everything for everybody, and nothing will ever be the same again. As soon as you have an idea that changes some small part of the world you are writing science fiction. It is always the art of the possible, never the impossible.

Imagine if sixty years ago, at the start of my writing career, I had thought to write a story about a woman who swallowed a pill and destroyed the Catholic Church, causing the advent of women’s liberation. That story probably would have been laughed at, but it was within the realm of the possible and would have made great science fiction. If I’d lived in the late eighteen hundreds I might have written a story predicting that strange vehicles would soon move across the landscape of the United States and would kill two million people in a period of seventy years. Science fiction is not just the art of the possible, but of the obvious. Once the automobile appeared you could have predicted that it would destroy as many people as it did.

INTERVIEWER

Does science fiction satisfy something that mainstream writing does not?

BRADBURY

Yes, it does, because the mainstream hasn’t been paying attention to all the changes in our culture during the last fifty years. The major ideas of our time—developments in medicine, the importance of space exploration to advance our species—have been neglected. The critics are generally wrong, or they’re fifteen, twenty years late. It’s a great shame. They miss out on a lot. Why the fiction of ideas should be so neglected is beyond me. I can’t explain it, except in terms of intellectual snobbery.

But why do I recommend you read such interviews when, quite possibly you are focused on just trying to write? Or don’t give a damn.

Well, apart from their intrinsic entertainment value—which is considerable—they help you understand and appreciate the mindset of a writer, and what all of us tend to have to go through at some time or other. Here I refer to rejection by publishers, shabby behavior by agents, terrible reviews in the press, factually incorrect criticism, long periods of waiting, financial uncertainty, editors without manners, family difficulties—and much more besides. Foreknowledge of such matters won’t necessarily mean you can avoid them, but at least you are likely to be better prepared.

Beyond that, it is vastly consoling to know that such unfortunates survived the hazards of our generally precarious existence, and went on to fame and—in many cases—to adequate financial security.

Fundamentally, THE PARIS REVIEW INTERVIEWS make the writer—published or otherwise—feel a little less alone—and, above all, they encourage.

George Plimpton died in 2003. It warms my heart that the fine traditions he established live on.

No comments:

Post a Comment