Writing, to me, is simply thinking through my fingers.

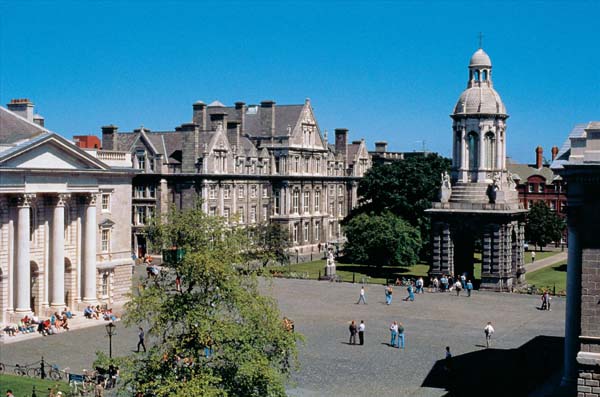

MY UNIVERSITY: TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN.

IT WAS FOUNDED WHEN ELIZABETH I WAS QUEEN (1592) AND DINASAURS RULED THE EARTH. THEY STILL DID WHEN I WAS THERE 1960-64.

When I was at university—I have a Masters—I studied Economics, English, and History. Economics was my main subject, but I took English as well because I hoped it would help me to write better.

It did nothing of the sort.

Its focus was on studying literature—analyzing books in excruciating detail—not on writing. I learned what eminent critics thought about famous books, but never had a single lecture on how to structure a story. To do well required remembering the words of wisdom of numerous critics verbatim—plus being able to quote from the books in question—something which did not play to my strengths.

As I have said elsewhere, I suffer from a form of dyslexia and have never been good at learning by rote. I tend to remember by association—and am quite good at that. I also have excellent recall of mood and circumstance. The odd phrase apart, I am a klutz when it comes to remembering anything verbatim.

I grew to dislike the subject, did the minimum to pass, and focused on Economics and History—both subjects I loved (and still do). In fact, I wrote at much greater length about Economics and History than I ever did about literature.

As I have explained elsewhere, there is a great deal more to writing than merely knowing how to write. In particular, you need:

- Extensive experience of life (so you have something to write about).

- To have read widely and well (and to continue to do so).

- How to research (including interviewing—which requires a range of interpersonal skills in itself).

- How to manage large quantities of data (No small issue as far as I am concerned. I am a data pack-rat).

- To have knowledge of, and be committed to, the lifestyle. (sitting alone in front of a computer all day strikes many people as somewhere between weird and unnatural)

- The fortitude to endure decades of failure and severe financial stress. (Failure in the sense that you will rarely write as well as you want. Financial stress because you don’t get a regular predictable paycheck—though some us do well).

- Considerable knowledge of the book business. (This is more difficult to come by than you might think. Agents and traditional publishers like to keep their authors ignorant—because an ignorant author tends to be less demanding. ).

Nonetheless, if you want to write a book, it helps to know certain specifics.

- How to plot and structure a story—including writing an outline. (I used to hate plotting. Now I love it. I still hate outlines.)

- How to pace a story. (A reader should never get bored).

- How to build in suspense. (This is technique—but important).

- Character development. (If you get your characters right, they practically write the story).

- Exposition. (Editors hate exposition because they feel it slows the story down. Speaking as a reader, I rather like it because I learn more of what is going on)

- How to make your book entertaining. (This is THE most important thing).

I didn’t learn any of these things consciously. Perhaps I should have—but the truth is that I have learned almost everything I know about writing through reading—though osmosis if you will.

If you read (and comprehend) enough, you cannot help but absorb a great deal—and if what you read is well written, your own writing will improve accordingly. It helps greatly to be well informed because you will gain more from a book if you know the context. The more you know, the more you will learn. The process builds upon itself, but benefits from a foundation of knowledge. Re-read a book years later and you will learn much that was hidden the first time around.

The secrets of writing are hidden in plain sight. They just require prodigious dedication to tap into. Successful reading takes time and effort—and a certain quality of mind. In fact, reading—and comprehending—in itself is a skill (typically one that is under-appreciated).

In my favor, let me say that I read prodigiously—typically about three books a week—and across a wide range of subjects—and I read with some intensity. In fact, I tend to become deeply involved in whatever I read—assuming it is of reasonable standard. As for ensuring that, I became an expert book browser at an early age—and am rarely disappointed with what books I pick—even if I am unfamiliar with the author.

It really is quite uncanny—and I’m not quite sure how I do it. I scarcely rely on book reviews at all. Typically, what guides me is subject matter and skimming a few pages. If the writing strikes the right note, I’m off to the races.

I did buy a number of books on how to write—but, to be frank, found them boring so never gave them the attention they probably deserved. Shame on me. Instead I would revert to a novel—or some non-fiction work about a topic that interested me. I prefer to be entertained as I learn.

If I didn’t read ‘How to Write’ books, I did read a great many books about writers—together with every interview I could lay may hands on. I found such reading inspirational and fascinating.

Writers, like movie directors, generally talk well, and are entertaining. That should scarcely be a surprise. Most are worldly, intelligent, and thoughtful—and, if you want to stay sane in the writing game, you need a sense of humor. They also tend to be both empathetic and observant.

Though I didn’t have a writing mentor as such—in the sense of an experienced writer who would teach me the craft—I did have a very good writer friend who I would talk my thoughts through with.

Though I didn’t have a writing mentor as such—in the sense of an experienced writer who would teach me the craft—I did have a very good writer friend who I would talk my thoughts through with.

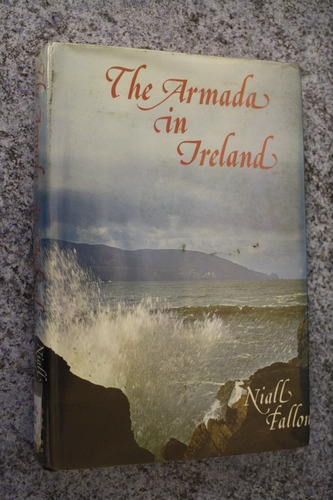

He was Niall Fallon, a deputy editor of Ireland’s newspaper of record, the Irish Times, and a non-fiction writer of some distinction in his own right.

Niall was a wonderful man, with an acerbic sense of humor, who would have loved to have become a full time writer himself, but who was constrained by family commitments and his excellent job at the Times. He was paid too much money to quit—and said so. His situation excoriated him.

I would go and stay with Niall frequently—and we would walk and discuss issues, but would always come back to writing sooner or later. Niall would never tell me how to write, or get involved in the specifics of a plot, but he did a great deal to prepare me for the level of commitment involved—yet was consistently encouraging.

Whereas many people seem to regard writing as a feckless occupation because of the lack of financial security (though, paradoxically, successful writers are treated as if they walk on water) he regarded it with great esteem—and thought it was worth risking everything for (providing you didn’t have a family dependent on you).

He was well qualified to empathize with my goal.

He had taken leave of absence from his job for a period and, with his family, had lived in the West of Ireland while working on THE SPANISH ARMADA IN IRELAND. He didn’t recall the period with much affection—and had thoroughly disliked living in the West of Ireland.

I located my protagonist, Hugo Fitzduane there nonetheless because the West has very special romantic associations for me—and it is beautiful in a wild and windswept kind of way. Yes, it does rain too much—and the constant wind off the Atlantic will tan you faster than the South of France (wind burn), but the terrain will grip your soul.

His excellent book had earned him a great deal of respect, but not a great deal of money. Nonetheless, writing it had been extraordinarily important to him.

While not minimizing the financial stresses involved—in fact he emphasized them—it was Niall who consistently advocated that writing should be a full time job.

It was too serious and demanding a business to dabble in. He was adamant on that point. I didn’t need much persuading. I had already formed the same view. Nonetheless, it was comforting to have my opinion reinforced.

Niall wasn’t always the easiest of men—he liked to challenge, which was part of his attraction as far as I was concerned. He would stretch me mentally—and vice versa. We had a candid relationship based upon mutual affection and respect—and much humor

Tragically, he died of a heart attack way too soon—the day after a physical that gave him the all clear. He was still in his fifties.

To say we were appalled doesn’t get close. I still think of Niall constantly and I can hear his voice slagging me over something or other. ‘Slagging’ is joshing in Ireland—and very much part of the culture. If you can’t hold your own, you had better emigrate!

Niall was an inveterate slagger—but never vicious. There was always the quizzical smile and the warm tone of voice.

I can hear him now. He had a very distinctive voice. He was a man to love—and he was much loved. It is hard in our culture to say this about a man—but I loved him.

Niall was, as we say in Ireland, a thoroughly decent man who enriched the lives of all who knew him. I have numerous wonderful memories of him—mostly humorous and all heart-warming—but my favorite happened when I took my children down to visit him, and some other friends, at a rented holiday home in Kerry.

As fate would have it, my children were regarded as intruders. This was the first time we had visited—whereas the others had been going there for years, and had formed a tight little clique.

My kids were not made welcome.

Predictable but unpleasant.

Time might have overcome this, but since we were only visiting for a couple of days, there wasn’t much point in doing anything too drastic—but Niall could see that I was somewhat upset.

The following day he avoided friction by letting the clique do its own thing—while he took me and my kids on a long walk through the very beautiful Kerry countryside.

We ended up by climbing a steep hill—we probably called it a mountain, but Ireland has few serious mountains—and, somewhat puffed, sat down to recover, and gazed across the truly spectacular view.

It was a hot day (by Irish standards). Niall then produced soft drinks and sandwiches—and a liter bottle of wine for the pair of us (and glasses).

He knew I was partial to wine, and without saying a word, had lugged that weight just so he could surprise us—and me in particular. The gesture was part apology and part hospitality—and all Niall.

Wine has rarely tasted better. The unpleasantness of the previous day—which I had understood if not liked—was forgiven and forgotten. I think we drank most of the wine. I know we stayed on that hilltop for a considerable time, just talking. I was much moved. It was very special.

Such was Niall—mentally tough, challenging, kind, vastly intelligent, empathetic, thoughtful, generous, warm hearted—and witty.

True, I didn’t have a writing mentor. I had something better still—the very best of friends (who happened to be a writer).

I have said elsewhere that a writer only needs a single supporter to make it—but you really, truly, and absolutely need that one person.

The alternative is despair—and probably death—and that’s no way to run a railroad.

However it appears, no one does anything entirely alone. We all have backing in some way or other. Backing of the spirit may be the most important type of support. Typically it says:You can do the impossible—and such a statement has the effect of galvanizing you into effective action. To be believed in is just plain wonderful. Such belief may well not last—people are not good at long distance—but it buys you time. You limp from lily pad to lily pad. You endure.

Eventually—and it can take a ridiculous amount of time—you achieve.. Few understand. It is worth every second.

Writing—unless you are very successful—does not make for an easy life. When I have wavered—or temporarily lost my way (as I have)—I have always had my courage restored by a friend.

A hand has been extended and I have been hauled to my feet (feeling somewhat mortified, may I add).

I feel much blessed in that regard. I do not take it for granted. I hate to fail in such an abject manner—it’s humiliating—but better to fail and be humiliated than to give up. The one is a small victory—but a victory nonetheless.

Let me add that all my writer friends have been consistently supportive. They understand in a way most others do not. Though they are mostly a successful bunch, they have all endured hard times too. They know the value of support and give it willingly.

Writers are supposed to be jealous of each other. I have yet to see any evidence of it. Empathy has tended to dominate.

I still don’t have a writing mentor. In fact, I’m working up to mentoring others. However, I am fortunate enough to have a friend who has many of the same qualities as Niall.

Is he also a writer?

Surprisingly not—yet he understands my arcane writing world in a way that few do. He is a former Apache AH-64 attack helicopter who I met originally when I was researching the 101st Airborne back in the mid Nineties—nearly 20 years ago.

And yes, I did fly in an Apache AH-64 attack helicopter both by day and by night—a singular honor—and, as it happens, a life changing experience.

His name is Tim Roderick—now a retired Chief Warrant Officer Four—and if I have any further success in writing, it will be due in no small measure to him. According to Tim, WOs are the problem solvers of the Army. They tend to be specialists and to know their fields better than most. Warrant is an interesting rank. I suspect he is right.

Do writing and flying attack helicopters have anything in common?

Both require total commitment and are particularly demanding occupations. Both require solving numerous problems. Both can, at times be exceedingly dangerous (if you research the kind of stuff I do). That said, attack helicopters get shot at more. But they can shoot back—and that they certainly do.

Writing is a strange business—and puts us in strange, dangerous, and wondrous places.

Now you know.

No comments:

Post a Comment