YET ANOTHER EXAMPLE OF INSTITUTIONAL NASTINESS—THOUGH I AM NOT SURE THAT IS AN ADEQUATE PHRASE BECAUSE SUCH BEHAVIOR CAN HAVE DEVASTING CONSEQUENCES.

IN THIS CASE, IT CONCERNS AN HONORABLE MAN TRYING TO DO THE RIGHT THING—AND BEING SHAFTED BOTH BY HIS OWN SERVICE, THE ARMY, AND THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE.

I’m never quite sure whether large organizations attract and breed careerists—or whether careerist have a tendency to gravitate towards such institutions. Operating with the cover of organization of size blurs individual accountability and tends to mean that dubious behavior is lost in the bureaucracy.

Either way, it is a readily observable fact that large organizations have a depressing habit of behaving badly—unless led by unusually good leaders (and, fortunately there are many which fall into that category—just not nearly enough).

Good leadership is the exception. I find it hard to stress that too much.

Most organizations are led by people of mediocre caliber, and even less integrity—which explains a great deal about the state of society today. The U.S., in particular, has never been richer or had access to such resources (financial, material, and intellectual) yet done such a miserable job for most of its population.

The economy is sluggish, productivity is poor, innovation is down, most workers are less than happy with their jobs, poverty is rife, whole sectors of the economy are a disgrace by international standards, and the political system has been suborned by a tiny ultra-rich minority.

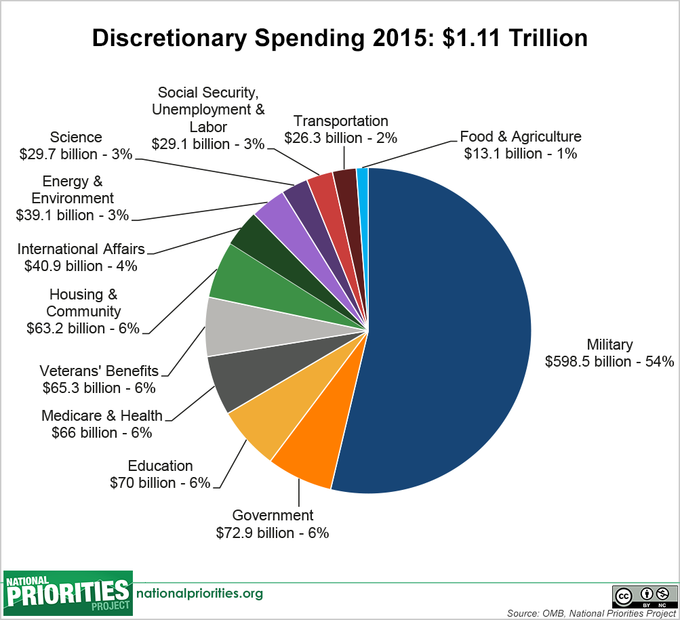

On top of that, despite having the most powerful military in the world, we seem singularly unable either to win our wars, or even to end them in any remotely satisfactory way—if at all. In fact, you can make a very good case that some very powerful people, who make a great deal of money out of unending war, don’t want such conflicts to be concluded—and work hard to see that they are not. The power and corruption of the MICC (the Military Industrial Congressional Complex) should not be underestimated—nor should their ability to block, contaminate, and metastasize. The influence of the MICC extends way beyond the military area. In practice, it functions as a substantial component of the interlocking political control system constructed by the ultra-rich.

Careerism makes no small contribution to this unnecessarily unsatisfactory situation.

I have written about careerism many times in the past, but essentially it is a pattern of behavior which involves putting self-advancement before integrity and the mission—and being willing to do virtually anything if it serves that self-centered purpose. The right thing has no meaning in this context. A moral code is irrelevant. The concept of the decent thing is risible. All that counts is the expedient—the career-advancing—thing.

Normally, doing “virtually anything” involves making one’s bosses happy, regardless of the issues, and covering their asses—after making sure one’s own is covered first—in the process.

Keeping one’s bosses happy covers a multitude—but consistent practices in pursuit of that goal include:

-

Re-interpreting events (lying) to put one’s bosses and the organization in a positive light.

-

Suppressing bad news where possible.

-

Suppressing any and all initiatives, making no decisions, and changing nothing because, by definition, if you retain the status quo, neither you nor your bosses can be accused of doing anything wrong.

-

Blocking exceptional talent, where possible, because exceptional talent has a tendency to show up both oneself, and one’s bosses, adversely.

-

Blocking anyone who tries to rock the boat in any way—even if his or her cause is demonstrably good, and they are clearly acting with the best of intentions.

Careerism is not confined to the military. It is common to virtually all large organizations, from corporate to academia—and it constitutes a core component of the current American Business Model—but it is particularly evident in the military, with results which are clear to see.

Where the Pentagon is concerned, careerists tend to gravitate towards being senior officers’ aides—since that guarantees them mentors, an inside track to the various clubs that make up Higher Command, and an exposure to the go-along to get-along culture that pervades the system—and which can detect non-conformists in a heartbeat.

The system requires a degree of competence, but has almost no interest in talent—except in rare situations when it is needed—but it positively excels at identifying anyone who won’t fit in. Indeed, you don’t have to do anything to be spotted as unacceptable. The one truly remarkable ability of nearly all careerists is that they seem to be endowed with a downright uncanny ability to sniff out, and oppose, a decent human being.

Decency virtually guarantees career death. If you are in the military, regardless of your talent and demonstrated heroism, unless you are a careerist, it is virtually certain that you will never make it past the rank of colonel. There are rare exceptions to this—but they are just that—rare.

The club of generals seeks careerism, competence, and conformity to the status quo. Courage is not a requirement—and both physical and moral courage may be a detriment, especially if demonstrated in such a way that has attracted attention. In Japan, the nail that protrudes is hammered down. Where the U.S. military is concerned, it just doesn’t get promoted. That said, it will probably get hammered too.

Careerist are not unpleasant people to meet—and are not necessarily bad people in their private lives. Virtually all are personable, most are reasonably intelligent, and many are good company and are regarded as “good guys.” But they have sold out—and though this lack of integrity can be hard to detect at the level of individuals, it is manifest where institutional behavior is concerned.

The case of Colonel Jason Amerine is yet another depressing example. Disturbing enough in itself, we should worry a great deal more about what this treatment of Colonel Amerine implies—particularly about the leadership.

The following story is from the Washington Post of June 11 2015.

Special Forces officer: American hostages held overseas ‘failed’ by U.S. government

Washington’s effort to recover American hostages held overseas is “dysfunctional” and mired in failures hidden by bureaucracy, an Army Special Forces officer once involved in the Pentagon’s part of the mission told the Senate on Thursday during a hearing for whistleblowers.

Lt. Col. Jason Amerine is shown here at Arlington National Cemetery. (Photo released by the office of Rep. Duncan Hunter)

Lt. Col. Jason Amerine testified that he started working on hostage policy at the Pentagon in early 2013. At some point, he became frustrated with the inaction to free Americans and said he took his concerns to Rep. Duncan D. Hunter (R-Calif.), a member of the House Armed Services Committee, after exhausting all other options. The Army, when it learned about his discussions on Capitol Hill, responded by removing him from his job, suspending his security clearance and launching a criminal investigation into his actions, Amerine said.

“My team had a difficult mission and I used all legal means available to recover the hostages,” Amerine said in prepared testimony. “You, the Congress, were my last resort. But now I am labeled a whistleblower, a term both radioactive and derogatory. I am before you because I did my duty, and you need to ensure all in uniform can go on doing their duty without fear of reprisal.”

Amerine testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee during a hearing called “Blowing the Whistle on Retaliation: Accounts of Current and Former Federal Agency Whistleblowers.” He first acknowledged facing an Army investigation and communicating his concerns about U.S. hostage policy to Hunter in a Facebook post on May 15.

The case pits one of the first heroes of the Afghanistan War against the Army. Amerine led a Special Forces team there in 2001 that protected future Afghan President Hamid Karzai. Amerine was wounded by an errant American bomb on Dec. 5, 2001, that killed three other Special Forces soldiers. He later received the Bronze Star with “V” and the Purple Heart, and was labeled by the Army as a “Real Hero” in the 2006 version of its popular video game, “America’s Army.”

The Army Criminal Investigation Command (CID) has disputed that it is investigating Amerine as an act of reprisal, and declined to say whether the soldier is under investigation at all. A spokesman for CID, Chris Grey, declined to comment Thursday on Amerine’s testimony.

Amerine told the Senate that in 2013, his office at the Pentagon was asked to help recover Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, the U.S. soldier held captive for five years overseas and charged earlier this year with desertion. He was later recovered May 31, 2014, in a controversial swap for five Taliban officials.

In this file image taken from video obtained from the Voice Of Jihad Website, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl sits in a vehicle guarded by the Taliban in eastern Afghanistan. He was recovered in a swap for five Taliban officials last year. (AP Photo/Voice Of Jihad Website via AP video, File)

“We audited the recovery effort and determined that the reason the effort failed for four years was because our nation lacked an organization that can synchronize the efforts of all our government agencies to get our hostages home,” Amerine said. “We also realized that there were civilian hostages in Pakistan that nobody was trying to free, so we added them to our mission.”

Amerine’s team worked to develop a viable trade for Bergdahl, bring the Taliban to the negotiating table and fix the interagency recovery efforts, he said. He “used all legal means” available to recover the hostages, and then went to Congress when he ran out of other options, he said. That prompted the FBI to complain that he was sharing classified information, he said. The Defense Department inspector general later determined he did not, he added.

Amerine credited the Defense Department inspector general with handling a reprisal complaint he filed well. The FBI has previously declined to comment on Amerine’s allegations.

Amerine credited Hunter with influencing the Pentagon to appoint Michael D. Lumpkin, a retired Navy SEAL and current deputy undersecretary of defense, as the Defense Department’s hostage recovery coordinator. Doing so allowed the Pentagon to respond quickly when a deal was struck to recover Bergdahl in exchange for five Taliban officials, Amerine said.

But the other civilians held hostage — including Warren Weinstein, who was accidentally killed in a U.S. drone strike in January — were left behind, Amerine said. One of the options Amerine’s team developed would have swapped seven Westerners for one Taliban drug trafficker and warlord: Haji Bashir Noorzai. He was convicted of drug trafficking and sentenced to life in prison after being lured to the United States in 2005.

Amerine told the Senate that the trade developed would have freed Bergdahl, Weinstein, Canadian Colin Rutherford and a family of three: Canadian Joshua Boyle, his American wife Caitlan Coleman, and their child born in captivity. He declined to identify the seventh hostage.

It’s unclear how the Noorzai swap would have worked. Bergdahl was held by insurgents affiliated with the Taliban, while Weinstein was held captive by al-Qaeda.

“Is the system broken?” Amerine asked. “Layers upon layers of bureaucracy hid the extent of our failure from our leaders. I believe we all failed the commander in chief by not getting critical advice to him. I believe we all failed the secretary of defense, who likely never knew the extent of the interagency dysfunction that was our recovery effort.”

This image made from video released anonymously to reporters in Pakistan on Dec. 26, 2013, shows American aid worker Warren Weinstein. He was held captive in Pakistan until he was mistakenly killed in a U.S. drone strike in January. (AP Photo via AP video)

Hunter said on the House floor last month that Amerine was critical in providing information that helped craft a congressional amendment that would require President Obama to appoint a specific federal official to oversee all hostage recovery efforts.

“Lieutenant Colonel Jason Amerine has worked with my office now for about two years on this amendment, and he is someone that really cares,” Hunter said. “He’s been working hostage stuff with about every government agency that there is, and he played a big role in getting this to where it’s at now.”

Amerine said he “failed” Weinstein and the four other Western hostages still in captivity.

“We must not forget: Warren Weinstein is dead while Colin Rutherford, Josh Boyle, Caitlin Coleman and her child remain hostages,” Amerine said. “Who’s fighting for them?”

Dan Lamothe covers national security for The Washington Post and anchors its military blog, Checkpoint.