People show courage in all kinds of ways—and far more often than perhaps we appreciate.

People show courage in all kinds of ways—and far more often than perhaps we appreciate.

Do we give it enough credit? Probably not. It is one of the more admirable human qualities, and it’s all around us. It takes considerable courage just to live.

Where dying is involved, you don’t have much choice in the matter—though you need it in spades when attending the dying.

Inevitable or not, I have witnessed incredible courage from the dying. If I can die as well as Jo Curran, who I helped to look after several years ago as she was dying of cancer, I will have met the highest standard.

When I was young, physical courage seemed to be the main focus. It was the most talked about and respected at boarding school—and it was an underlying theme in many of the books I read; and in virtually all movies.

This caused me some concern. It did not seem to me that I was physically brave—and having a vivid imagination doesn’t help—and I suffer severely from vertigo. Meanwhile, my peers were doing all kinds of daring things—from rock climbing to scuba diving—and seemed to be relatively immune to fear.

I thought about this quite a bit because for some time it seemed inevitable that I would join the Army. Compulsory National Service (conscription)—was still in force—and the chances of seeing action in those days were high as one dirty little war followed another. Malaya, Kenya, Borneo, Egypt, Cyprus, Aden—the winding down of the British Empire was scarcely a peaceful business. It was bloody. The Northern Ireland Troubles hadn’t started then—though they flared up in a few years. Then, since I lived in Ireland, I had a war I could commute to.

I was reminded of an epic line from a Robert Mitchum movie—whose title I forget. In it, he climbs into a taxi and says: “Take me to the war.” Now that is cool. I never expected it to become my reality.

How would I cope when under fire? The ultimate pejorative term was to be called a coward.

As it happens, conscription was abolished so I never had the chance to find out how I would have fared in the military. And I certainly didn’t intend to volunteer for further years of boarding-school type discipline, topped up with incoming gunfire coming from people I had no desire to kill.

Over the decades, I have spent considerable time with various military units—and have even enjoyed the dubious pleasure of coming under fire and being in danger in other ways—and have found that there is much that is attractive about that world (apart from being shot at). But I have never regretted my decision to remain a civilian. It’s hard to let your mind roam freely in such a disciplined world.

This left vertigo to deal with. To resolve that, while I was security guard in London (a temporary job while I was a student) I climbed onto the roof of a skyscraper I was guarding, and stood on the very edge, my toes protruding, the wind gusting as I leant forward—and then looked down its 20 plus stories.

I still get the chills when I recall the event—and suffice to say it didn’t work, and may have been the stupidest thing I have ever done (and the competition is considerable). I still hate heights, though paradoxically I love small plane and helicopter flying—even when it’s dangerous.

Helicopters—ridiculous machines—are just plain special. But that is another story.

While at university, I began to appreciate moral courage—and to observe that it was decidedly less common than the physical kind. Even when some issue or other clearly demanded that one should take action, depressingly few people seemed willing to stand up to be counted. I didn’t understand that because my standard, in that area, was my much loved, and high-minded grandmother, who would speak to any just cause—within the orbit of good judgment—regardless of the odds. And who did so with considerable success; and no manifestation of self-righteousness. In fact, it was that lack of self-righteousness that was one of her most attractive qualities. She was an innately humble protagonist—and a magnificent human being.

Though I respect courage in all its forms, I admire moral courage the most. It’s what drives the search for a better way of life for us all—and it has an impressive track record. Often it is combined with physical courage—though not always. It can be exceedingly stressful and the price can be high. It’s less common for good reasons. It tends to be crushed ruthlessly in large organizations—and today we live in a world of large organizations.

Moral courage’s great enemy is careerism—which, loosely defined, means putting your own personal advancement ahead of what is clearly the right thing to do. It is currently rife in the U.S. I encountered it frequently in the Pentagon where there is a saying—about the officer corps—that many officers prefer to risk their life rather than their career.

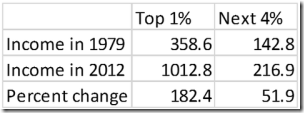

True? True enough unfortunately. Careerism (in essence, another word for greed) has become culturally acceptable—which helps to explain why the richest country in the world today tolerates neglecting the basic economic wellbeing of so many fellow Americans.

I find this inexplicable, unacceptable—and just plain bad business. If you so underpay your workforce that they can’t afford to buy the goods you make, the consequences are predictable.

I first became aware of courage in the creative area through the theater. I was much exposed to this world because various family members, and girlfriends, were involved with it—and it was because of this that I came to appreciate how much courage it took to act in front of an audience. In fact, some performers would throw up before going on stage, but would still do the deed. I found that impressive—and still do.

My one and only acting experience was in JULIUS CAESAR while at school. There I had to make one speech—while on bended knee—and then help to carry Caesar’s corpse off stage. I was a slave. The only trouble was that the wings were not really deep enough to conceal us stretcher-bearers and the stretcher—so the first stretcher-bearer had to step into a circular staircase that ran to the floor below. That worked well enough during rehearsals, but on the day of the performance the tempo was somewhat brisker—and I inadvertently pushed the first stretcher-bearer, the stretcher, and Caesar’s corpse down the stairs. Unsuitable language and my laughter punctuated Shakespeare’s fine words. Being dead didn’t hinder Caesar on jot.

The most tempting aspect of the theatrical world, as far as I was concerned, was that it provided access to pretty girls and beautiful women—sex in a word—but since I had access to the theatrical milieu though my girlfriend, I was never seriously tempted. I didn’t have the looks, the acting talent, or the temperament. Besides, when it came to standing up in front of an audience, I was unashamedly a coward. Not entirely true. I admire the courage of actors—something we mostly take for granted—and am ashamed in their contrast. Acting takes guts.

Paradoxically, I have come to enjoy public speaking, and have become quite good at it. Although I am sure my technique can be improved, I can hold and entertain an audience—and particularly enjoy the Q&A aspect. So what’s the difference between public speaking and the theater? In the former, you have considerable flexibility and can trust to your wits. Where the latter is concerned, you have to know your lines—and I have never had much talent for rote learning.

Does writing require courage? In terms of economic risk, it most certainly does. In fact, in that context, it’s a high-wire act with a long drop, and without a net. But, it doesn’t stop there. You also have to face the fact that you are putting your best efforts forward to be judged by millions of people—if you are lucky—and possibly eviscerated by critics. And the publishing world itself can be brutal. So, yes, it does take courage—a very special kind of courage—to be a writer. Special because you have to remain brave (or pretend to be) for long periods of time; and that is particularly tough. Fear has a cumulative impact.

I gained that insight in Northern Ireland when I was rammed up against a wall, a sub-machine gun in my back, by a patrolling soldier—his section backing him up. What the f—was I doing walking in Belfast at four in the morning? I have no idea what I said in reply. I will ever remember the sweat of fear on his rawboned face. He had to patrol night after night—never knowing when a sniper would take him out.

The truth is that having been in one gunfight, I was looking for more action. Madness in retrospect. Bur I was on an adrenalin high.

But, one good thing about book-writing is that you can take as long as is necessary—within reason—to polish your work to an appropriate standard—and thus minimize the risk of being skewered.

Blogging is high risk because it’s spontaneous, revealing, and there isn’t really the time to edit out your errors—especially if you blog frequently.

For these and other reasons, I didn’t take to blogging initially—and blogged somewhat erratically. I then began to appreciate that if writing is fundamentally about “illuminating the human condition,”—which is the standard I hold to—then revealing one’s flaws, fears, and imperfections is a risk one has to take.

For these and other reasons, I didn’t take to blogging initially—and blogged somewhat erratically. I then began to appreciate that if writing is fundamentally about “illuminating the human condition,”—which is the standard I hold to—then revealing one’s flaws, fears, and imperfections is a risk one has to take.

The truth—honesty if you will—is what makes the best form of communication work—and writing is the high ground of communication. Seeking out one’s own truth is a serious, and rather frightening, commitment—even with a little humor thrown in.

Does it make sense? If that was my standard, my life would be very different. But, it’s a great adventure—and what else is life, but an adventure—a magnificent adventure, with a beginning, a middle, and an end?

Life is a story.

Besides, right now, I haven’t the courage to stop.

Given the amount I read and write about the economy, you would think I would have run across the term ‘precariat’ before. After all, I’ve written about the condition on a number of occasions. But, somehow I missed the actual word until now.

The corporation, which keeps keeps your hours down (typically to avoid having to pay you some benefit or other), yet insists you be on call—unpaid of course—just in case you are needed, is turning you into a precariat.